Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer, Portrait of Georges Rodenbach

Colour etching after a pastel, 1930

I first came across the riveting pastel portrait of the Belgian Symbolist novelist and poet Georges Rodenbach by his friend Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer in an entry in Jane Librizzi’s arts blog, The Blue Lantern. The pastel was executed in 1895, and shows the dandyish author dishevelled and wild-eyed, seemingly rising – or even resurrecting - from a canal in front of a backdrop of gabled roofs and cathedral towers. Although Rodenbach was very much alive, the portrait is an intimation of his early death, in 1898 at the age of 43. Rodenbach looks already lost. It is, as Alan Hollinghurst writes in his perceptive introduction to the Dedalus edition of Rodenbach’s decadent masterpiece Bruges-la-Morte, a kind of double portrait of Rodenbach himself and of Bruges-la-Morte’s central character Hugues Viane, a widower driven mad by grief and desire. Now in the Musée d’Orsay, this striking pastel is today Lévy-Dhurmer’s most celebrated work. It’s all the more remarkable in that the precisely observed Bruges townscape in the background was all done from photographs, Lévy-Dhurmer having never – at this point – visited Bruges.

Georges Rodenbach

Until Jane piqued my interest, I had not paid Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer much attention. I already owned a single lithograph, Belle d’antan, published in 1897 by L’Estampe moderne. The generic wistfulness of this image doesn’t much appeal to me, and I had Lévy-Dhurmer down as a minor Symbolist of little originality or importance. The link with Rodenbach suggested a more subtle and intriguing artist, and so I began investigating what else could be found out about him.

Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer, Belle d'antan

Lithograph, 1895

Lévy-Dhurmer was born in Algiers, into a Jewish family. His real name was Lucien Lévy, to which he added a corruption of his mother's maiden name, Goldhurmer, to differentiate himself from other artists named Lévy. Although he did not attend the Beaux-Arts, Paris, as a regular student, Lévy-Dhurmer benefited from advice and encouragement from several teachers there, including Raphaël Collin, Vio, and Wallet. He first exhibited at the Salon des Artistes Français in 1882; however the need to earn a living prevented him from devoting himself fulltime to fine art. From 1887-1895 Lévy-Dhurmer worked as artistic director of the ceramics factory of Clément Massier, becoming known for his experiments with metallic lustre glazes and for his Islamic-influenced Hispano-Moresque designs.

Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer, Tower in Bruges

Colour etching after a pastel, 1930

It was not until 1895 that Lévy-Dhurmer returned to Paris, to take up painting full time. His paintings and pastels of melancholy women, in a dreamy Symbolist style, exhibited at the Galerie Georges Petit in 1896, were a success both with the public and his fellow artists. From 1906, Lévy-Dhurmer exhibited regularly at the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts.

Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer, The two women had fused into one

Colour etching after a pastel, 1930

Around 1910 Lévy-Dhurmer also became interested in interior design, and the Art Nouveau concept of the interior as an integrated and coherent work of art. The magnificent Wisteria Drawing Room that he created in 1910-1914 for his friend Auguste Rateau is now on display in the New Galleries for 19th and early 29th Century European Paintings and Sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, after decades in store.

Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer, Trees in Bruges

Colour etching after a pastel, 1930

In his later years, Lévy-Dhurmer abandoned overt Symbolism, but he remained committed to the Symbolist aesthetic of using art to open a window into another world; he was particularly interested in finding a visual correlative for music. In 1973 a major exhibition at the Grand Palais, Autour de Lévy-Dhurmer, placed his art in the context of the period, and the work of other Symbolist and Intimiste artists, such as Ernest Laurent, Charles Cottet, Henri Le Sidaner, and Edmond Aman-Jean.

Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer, Procession of the Holy Blood, Bruges

Colour etching after a pastel, 1930

His friendship with Rodenbach in the last three years of the writer’s life was clearly important to Lévy-Dhurmer, and in 1930 he published an illustrated edition of Bruges-la-Morte, in which the feverish melancholy of this very 1890s text is brilliantly expressed in 18 pastels, interpreted as colour etchings with aquatint by René Lorrain. Lorrain, born in Nancy in 1873, was a pupil of Gustave Moreau at the École des Beaux-Arts, Paris, and therefore finely in tune with the Symbolism of both Rodenbach and Lévy-Dhurmer.

Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer, Swans in Bruges

Colour etching after a pastel, 1930

It is fairly clear from these moodily atmospheric etchings that Lévy-Dhurmer had by now visited Bruges and soaked up the atmosphere of haunted decay that Rodenbach imagines rising as vapour from the canals and falling as drizzle from the sky.

Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer, Canal in Bruges

Colur etching after a pastel, 1930

The book was published by Javal et Bourdeaux, Paris, as loose folded and gathered sheets in a cover and slipcase, in an edition of 170 numbered copies – 15 on Japon imperial, with 5 states of the etchings, 155 on vélin d’Arches, with 4 states of the etchings. The text was printed by Robert Coulouma, the etchings by Adolphe Valcke. To print these subtle colour etchings required great skill. Printing “au repérage” in this way needs successive copper plates to be printed in close registration. Keeping the paper in exactly the right place to print these overlapping images leaves tiny pinholes above and below the image, something avoided if all the colours are printed at once in the “à la poupée” method.

Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer, View across a canal in Bruges

Colour etching with remarque, after a pastel, 1930

This was not the first illustrated edition of Bruges-la-Morte; the first edition of 1892 had a cover by Fernand Khnopff and 35 sepia photographs, and there was also a 1909 edition with wood-engraved illustrations by Henri Paillard. But Lévy-Dhurmer’s must be the definitive treatment of this extraordinary text.

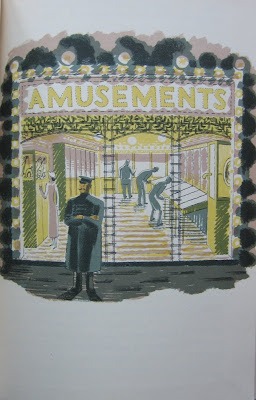

Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer, Building

Etching in green, after a pastel, 1930

I have been lucky enough to acquire an unnumbered hors-commerce copy – one of a few extra copies reserved for the artist and publisher – which is exactly as the 15 exemplaires de tête, i.e. printed on Japan paper, with the etchings in five states. These are: the definitive state in colours, interleaved with the text; a final state in colours with remarques; a state in blue; a state in green; and a state in brown. These last three states are not a decomposition of the various plates needed to form the colour images, but separate and sometimes highly effective interpretations of the pastels in shades of one colour.

Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer, Swans

Etching in blue, after a pastel, 1930

Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer, Tree

Etching in brown, after a pastel, 1930