Roger Vieillard, Économie dirigée

Engraving, 1934

Guérin & Rault 11 (state v/v)

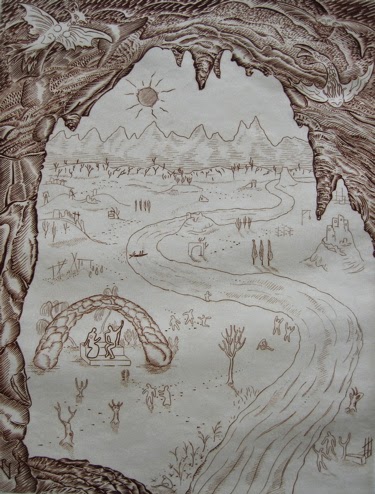

Vieillard devoted himself to the engraved line almost from the moment he entered Stanley Hayter’s famed Atelier 17 in 1934. He soon established himself as a master of copper engraving, specializing particularly in surreal mythological/architectural scenes, realized with great fluidity and imbued with a sense of mystery. He believed that engraving was capable of effects impossible to achieve in drawing or painting. The Surrealist atmosphere that prevailed at Atelier 17 in the 1930s is thoroughly ebedded in Vieillard’s work, though he seems to have avoided the factions and cliques of the Surrealist movement.

Roger Vieillard, Cité du Lac

Engraving, 1935

Guérin & Rault 97 (state vi/vi)

Interestingly. Vieillard’s wife, the American painter Anita de Caro, specialized in brightly-coloured abstracts, so the pair divided art up between them like Jack Sprat and his wife, he taking the line, and she the colour. A joint exhibition of the pair at the Propriété Caillebotte, Yerres, in 2008 was titled La Trait et la Couleur.

Roger Vieillard, Villes (Babylone)

Engraving, 1935

Guérin & Rault 86 (state iii/iii)

At Atelier 17 Vieillard studied alongside John Buckland-Wright, remaining on friendly terms with him. In England, the art of Roger Vieillard was also championed by the great expert on the livre d’artiste, W. J. Strachan, author of The Artist and the Book in France. Walter Strachan was influential in arranging two important exhibitions: a retrospective at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, in 1993 (with an excellent catalogue by P.M.S. Hacker, Gravure and Grace: The Engravings of Roger Vieillard) and the 1994 V&A exhibition Modern French Book Illustration: Vieillard, Flocon, Krol.

Roger Vieillard, Âge de fer

Engraving, 1948

Guérin & Rault 184 (state xvii/xvii)

Roger Vieillard, Fantaisie architecturale

Engraving, 1978

Guérin & Rault 605 (state v/vi)

The portfolio Architectures was published by Vieillard in 1980, “à la demande d’un groupe d’amateurs d’estampes”, in an edition of just eleven copies, of which nine were numbered 1-9 and two artist’s copies were marked A and B. It gathers together 14 engravings on architectural subjects, dating from 1934 to 1978. The engravings in the nine numbered copies are numbered out of the originally-envisaged editions of 30, 40, or 60, the artist never having printed the entirety of the stated editions. They were printed on very large sheets (in-folio raisin, 66 x 50 cm) of handmade Moulin de Larroque wove paper, in the atelier of the specialist taille-doucier Georges Leblanc. The small amount of type was hand-set and printed by Marthe Fequet and Pierre Baudier. My copy of Architectures is an out-of-series exemplaire de collaborateur, warmly inscribed by Roger Vieillard to Monsieur Baudier et Mademoiselle Fequet; the individual engravings are signed, titled, monogrammed, and marked “ép. col.”, collaborator’s proof. Presumably there was another exemplaire de collaborateur presented to Georges Leblanc, bringing the true number of copies of Architectures to thirteen.

Justification page of Architectures, inscribed by the artist

Roger Vieillard’s fascination with architectural forms persists right through his career. Some of his architectural fantasies are as complex as anything by Piranesi; equally he enjoyed simplifying these down to their essential structures, in what he called a “reprise linéaire”. I have three examples of this. Tour de Babel I was executed in 1935, while the reprise linéaire, Tour de Babel II, was created forty years later in 1975 (with the date 1935-1975 incised in the plate, in recognition of this engraving’s long gestation).

Roger Viellard, Tour de Babel I

Engraving, 1935

Guérin & Rault 28 (state vii/vii)

Roger Vieillard, Tour de Babel II

Engraving, 1975

Guérin & Rault 593 (state ii/vi)

My second example is also a Biblical subject, and again one that had haunted the artist for many years. It has its origins in a 1937 engraving of the blinded Samson destroying the temple of the Philistines, Chute du temple. In 1975 Vieillard engraved a new version of this, Ruine du temple (the major difference being the excision of a running female figure in the bottom right of the original composition, and a revised image of the god Dagon above the altar). His reprise linéaire of Ruine du temple is entitled Moment architectural.

Roger Vieillard, Ruine du temple

Engraving, 1975

Guérin & Rault 590 (state viii/viii)

Roger Vieillard, Moment architectural

Engraving, 1975

Guérin & Rault 591 (state iii/iii)

Lastly, Atelier and Espace d’atelier, both from 1973, envisages the artist’s working environment both as a hub of complex activity and as a tranquil negative space.

Roger Vieillard, Atelier

Engraving, 1973

Guérin & Rault 556 (state vii/ix)

Roger Vieillard, Espace d'atelier

Engraving, 1973

Guérin & Rault 557 (state iii/iii)

Two very interesting engravings from Vieillard’s later years are the almost abstract view of Manhattan, and the fully-abstracted Pyramide extrême. Manhattan is embodied by the Platonic idea of the skyscraper; I don’t think any individual buildings can be identified, and yet the place can be. Pyramide extrême similarly takes the idea of a pyramid to a state of geometric perfection. This engraving is printed from five plates—the central image and four long narrow rectangles along the sides.

Roger Vieillard, Manhattan

Engraving, 1966

Guérin & Rault 483 (state vi/vi)

Roger Vieillard, Pyramide extrême

Engraving, 1970

Guérin & Rault 513 (state iii/iii)

In a short foreword to Architectures, Vieillard sets out the reasons behind his fascination with buildings. He writes, Dès ses aurores, l’homme a conçu l’ARCHITECTURE comme le prolongement de sa vie brève et fragile, à la mesure de ses besoins et de ses songes, et l’a insérée dans une nature à lui offerte mais qui ne convenait pas à tous ses besoins. Elle fut d’abord son habitat, puis le décor des civilisations successives, le témoin de son passage et de ses modes de penser. “Since the dawn of time, man has conceived of architecture as a way of extending his brief and fragile life, by the measure of his needs and dreams, and has inserted it into a nature that was offered to him but did not meet all his needs. It was first of all a habitation, then the décor of successive civilizations, the witness of his time and of his way of thinking.”

Roger Vieillard, Cathédrale de Paris

Engraving, 1945

Guérin & Rault 130 (state vii/viii)

Beside Architectures, I have another rare set of engravings by Roger Vieillard, his Suite pour Déméter. This is one of twenty suites printed in bistre on Japon paper of a set of six engravings inspired by the Homeric Hymn to Demeter. Hymne à Déméter was printed in an edition of 250 (20 on Hollande and 230 on Lana), with 20 suites in bistre on Japon and 70 suites in black on Hollande. Mine is suite 6/20. The engravings were printed by Philippe Molinier on the hand press of Roger Lacourière. There are strong echoes of Surrealism in these really beautiful and graceful interpretations of the myth of the abduction of Persephone by Hades, the desperate search of her mother Demeter, the cyclical release of Persephone for the spring and summer, and the founding of the Mysteries of Eleusis.

Roger Vieillard, L'Enlèvement de Persephone

Engraving, 1946

Guérin & Rault 139 (state iv/iv)

Roger Vieillard, La Poursuite de Déméter

Engraving, 1946

Guérin & Rault 140 (state vi/vi)

Roger Vieillard, La Royaume des Morts

Engraving, 1946

Guérin & Rault 141 (state iii/iii)

Roger Vieillard, L'Incantation de Déméter

Engraving, 1946

Guérin & Rault 142 (only state)

Roger Vieillard, Éleusis

Engraving, 1946

Guérin & Rault 143 (state ii/ii)

Roger Vieillard, Vie & Mort de la Déesse - Les Saisons

Engraving, 1946

Guérin & Rault 144 (only state)

Roger Vieillard died in 1989. Like T. S. Eliot and Kenneth Grahame, he combined his artistic life with a successful career in banking, working at the Banque nationale pour le commerce et l'industrie (for which he was for many years the chief financial analyst, and latterly deputy director) in order to secure his financial independence and give himself complete artistic freedom. The exceptional purity of his artistic vision is perhaps partly due to this liberation from financial pressures.

3 comments:

These images are endlessly fascinating – I keep returning to them and I'm very grateful to have been given the opportunity to look at them.

This idea of the artistic freedom that can come, in the right circumstances, when a person has a high-flying career in business or banking or insurance is an interesting one. The extraordinary achievements of those two great American insurance men, Wallace Stevens and Charles Ives, are cases in point. Ives rewrote the rules of the life insurance business while forging a uniquely American musical style at weekends and on vacation. I am in awe.

Thanks very much for this comment, Phil - I had forgotten about Wallace Stevens, and I don't think I ever knew about Charles Ives. Vieillard's banking expertise is relevant to some of his engravings, such as Économie dirigée, which was marketed in the USA under the title New Deal - a classical structure tottering under its own weight.

I forgot to say, for anyone reading this, please click on the images to enlarge them - you can't really see them properly at the ordinary size. All of these engravings are quite large, and they are so highly detailed they need to be viewed at a larger scale.

Post a Comment