The contribution to graphic art made by the Curwen Press in the 1920s and 30s was immense. That story, and the continuing tale of the Curwen Studio, has been well told by Alan Powers in Art and Print: The Curwen Story (Tate Publishing, 2008), and Pat Gilmour in Artists at Curwen (Tate Gallery, 1977). But neither of these excellent books tells us much about Marion V. Dorn, who illustrated the first autolithographed book produced at Curwen, an edition of William Beckford's gothic orientalist novel Vathek, published by the Nonesuch Press in 1929. All of the illustrations to this post are original lithographs by Marion Dorn for Vathek.

Marion Dorn was born in the USA in 1896, and studied graphics at Stanford University. Having become interested in textile design in the early 1920s, she travelled to Paris with fellow designer Ruth Reeves in 1923, to explore the textile revolution being spearheaded by artists such as Raoul Dufy and Sonia Delaunay. There, she met the love of her life, fellow-American Edward McKnight Kauffer. They fell for each other hard. Kauffer left his wife and daughter for her, and they remained together until his death in 1954.

Ted McKnight Kauffer had already experienced professional success in England as a graphic artist, and Marion followed in his footsteps. Not that she wasn't a powerful talent in her own right, but it no doubt helped to have an "in" to a publisher such as Nonesuch, and a printer such as Curwen. Vathek proved to be Marion Dorn's only book project, and the 8 full-page illustrations and two vignettes are the only lithographs of hers that I have encountered. It's a shame, as they are quite beautiful. They are printed on a beige-coloured laid paper, and have the look of a pastel drawing. 1050 copies were published in the UK by Nonesuch, and 500 in the USA by Random House.

Why Marion Dorn did not continue with graphics after this is a bit of a mystery. Although she and McKnight Kauffer did collaborate on various projects, she may have been wary of treading too heavily on his toes.

Or it may be that the success she found as a textile designer - particularly of rugs and carpets - meant that her time was more fruitfully spent pursuing that line. In 1934 she founded her own company, Marion Dorn Ltd, which was wildly successful.

In 1940 Kauffer and Dorn moved back to the USA, neither to have quite the success back in their homeland that they had experienced in Britain.

Marion Dorn is an artist I would love to know more about. She strikes me as one of those women artists of the period - such as Enid Marx or Margaret Calkin James - who were edged out of fine art into the decorative arts, in a way that in the end enriched our culture and enabled them to fulfill themselves, but that was essentially unfair to their talent.

You can see, though, in the Vathek lithographs, a wonderful sense of design, especially in the repetition and variation of motifs, that would transfer readily to a rug, a furnishing fabric, a dress, or a wallpaper design.

Marion Dorn died in Tangiers in 1964.

Showing posts sorted by relevance for query Marion Dorn. Sort by date Show all posts

Showing posts sorted by relevance for query Marion Dorn. Sort by date Show all posts

Thursday, January 7, 2010

Sunday, February 7, 2010

What's in a name?

The name of Tirzah Garwood may well seem vaguely familiar, because it is unusual enough to stick in the mind. And I know some readers of this blog will recognize it immediately as the unmarried name of Tirzah Ravilious, who was married from 1930-1942 to the artist Eric Ravilious, and from 1946-1951 to Henry Swanzy.

Tirzah’s first wood engraving was made on 24 November 1926. By 1927 she was already exhibiting engravings at the Redfern Gallery, London. Over the next four years she was widely recognized as one of the most promising wood engravers of the day, and this at the height of the wood engraving boom. Her work received praise in both The Times and The New Statesman; examples were included in The Woodcut: An Annual for 1929, and (reproduced) in The New Woodcut, a special number of The Studio, in 1930; commissions flowed in from the Curwen Press, the Golden Cockerel Press, the Kynoch Press, and the BBC.

The title of Anne Ullmann's book is The Wood Engravings of Tirzah Ravilious. While I understand the reasoning behind the choice of title, there is a delicious irony here that my female readers will immediately grasp. For there are simply no wood engravings by Tirzah Ravilious. All her engravings were made between the ages of 19 and 23. After she married Eric Ravilious in 1930, she produced no more. Various reasons are given for this. It is nothing so simple as Eric standing in her way; indeed it was he who introduced her work to Herbert Furst, the editor of The Woodcut, and to Harold Curwen and others. Probably she simply found that she no longer had enough time to devote to such a painstaking art. But I suspect that, as with Marion Dorn and Ted McKnight Kauffer, there may have been a tacit wifely understanding that a sense of artistic rivalry might not be conducive to marital bliss. And her engraving The Wife, published three months before her marriage, implies, I feel, a certain fearfulness about what becoming a wife might entail.

Tirzah Garwood, Yawning

Wood engraving, 1929

Eileen Lucy “Tirzah” Garwood was born in 1908 into a conventional middle class background in Eastbourne, East Sussex. Attracted by the artistic life, at 18 she enrolled in a class in wood engraving at the Eastbourne College of Art. The teacher was Eric Ravilious, who was also born in Eastbourne, though by this time he was living either with Douglas Percy Bliss in London or with Edward Bawden in Great Bardfield.

Tirzah Garwood, Kensington High Street

Wood engraving, 1929

Tirzah Garwood, The Dog Show

Wood engraving 1929

There is a 1987 catalogue raisonné of Tirzah Garwood’s wood engravings, compiled by her daughter Anne Ullmann. Unfortunately I haven't been able to see a copy of this before writing this post; when I do, I may need to revise. It lists 43 wood engravings, the bulk if not the whole of a small but perfectly formed body of wittily observed and technically accomplished wood engravings.

Tirzah Garwood, The Crocodile

Wood engraving, 1929

The title of Anne Ullmann's book is The Wood Engravings of Tirzah Ravilious. While I understand the reasoning behind the choice of title, there is a delicious irony here that my female readers will immediately grasp. For there are simply no wood engravings by Tirzah Ravilious. All her engravings were made between the ages of 19 and 23. After she married Eric Ravilious in 1930, she produced no more. Various reasons are given for this. It is nothing so simple as Eric standing in her way; indeed it was he who introduced her work to Herbert Furst, the editor of The Woodcut, and to Harold Curwen and others. Probably she simply found that she no longer had enough time to devote to such a painstaking art. But I suspect that, as with Marion Dorn and Ted McKnight Kauffer, there may have been a tacit wifely understanding that a sense of artistic rivalry might not be conducive to marital bliss. And her engraving The Wife, published three months before her marriage, implies, I feel, a certain fearfulness about what becoming a wife might entail.

Tirzah Garwood, The Wife

Wood engraving, 1929/30

Following her marriage, Tirzah Ravilious’s artistic impulses were channelled into making beautiful marbled papers (see two lovely examples here), in collaboration with Charlotte Bawden (Tirzah and Eric were living with the Bawdens at Brick House, Great Bardfield). Then came the war. Eric Ravilious was lost over the Icelandic ocean while flying as a war artist observer on an air-sea rescue mission on 2 September 1942. Tirzah, was left a widow with three children, denied a war pension as her husband was not a combatant and his rank in the Royal Marines was honorary.Tirzah Garwood’s early promise was fulfilled not in art (though she did achieve wonders in her highly original marbled papers, and also make some small oil paintings, and some 3D paper sculptures) but in her marriage, her children, and her friendships. Even here, there was heartache. Eric Ravilious took a mistress, Helen Binyon; Tirzah developed breast cancer. She was recovering from a mastectomy when the news arrived of Eric’s death. After her remarriage in 1946 to Henry Swanzy, who worked for the BBC, her cancer returned, and she died in March 1951, at the age of 42.

Tirzah Garwood, The Big Man

Wood engraving, 1930/31

If this all sounds tragic, one has to set against it the memories of those who knew Tirzah as a vibrant and life-enhancing presence. Her friend Olive Cook, in an article on “The Art of Tirzah Garwood” published in Matrix 10 (the text of which is available here) remembered that, “After an absence of close on forty years her presence remains extraordinary and poignantly clear. Light boned and quick moving, she had the figure of a Botticelli angel, a pale, mobile, rather long face framed in wavy brown hair, a wide mouth and dark vivid eyes, shining with intelligence and full of half mocking humour.”

Tirzah Garwood, The Defeat of Apollyon

Wood engraving, 1928

I have been on the lookout for engravings by Tirzah Garwood; her work is, as you might expect, quite hard to come by. But I have managed to acquire impressions of 9 of her engravings. All of my prints are contemporary lifetime impressions, but in 1989 two of her engravings were reprinted from the blocks by Ian Mortimer at I.M. Imprimit in an edition of 500 copies for Merivale Editions. These were The Crocodile and The Dog Show - two of her finest works. These two, High Street Kensington and The Wife were all published in The London Mercury in 1930; they probably all date from the previous year. As I understand it, her last published engraving was the frontispiece she supplied for The Big Man by L.A.G. Strong, published in 1931, but probably executed the previous year.

Tirzah Garwood, Vanity Fair

Wood engraving, 1928

My earliest wood engravings by Tirzah Garwood are the three she made in 1928 for Granville Bantock's oratorio inspired by Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress, commissioned by the BBC. While these are strongly composed and show real talent, I can't feel that this commission played to her strengths. There is no room here for her gleeful observation of middle class life, so strongly present in my other examples of her work.

Tirzah Garwood, The Dream

Wood engraving, 1928

Except as the wife of Eric Ravilious, Tirzah Garwood has been almost forgotten. She has no place, for instance, in Albert Garrett's British Wood Engraving of the 20th Century. Patricia Jaffé's Women Engravers reproduces The Dog Show, but does not mention her in the text so far as I can see (there is no index). The only book I have that gives her her due is Joanna Selborne's wonderful British Wood-Engraved Book Illustration 1904-1940. Selborne describes the 8 prints completed by Tirzah Garwood for an unpublished Curwen Press calendar, to be titled Relations, as "probably her finest wood engravings and among the most vivid portrayals of 1920s middle-class life by a contemporary practitioner." Four of these subjects, illustrated above, are The Crocodile, The Dog Show, Kensington High Street, and The Wife. Olive Cook's article tells us that the "masterful figure dressed in the height of winter fashion" who is about to cross the road in Kensington High Street is one of Tirzah's aunts, near whom she was living in London while studying at the Central School of Art in 1929. The rather cowed girl trailing in her wake is carrying a briefcase marked with the initials T.G.

Monday, January 25, 2010

An English manner of going about art

There was a serious question behind the quiz in my last post, and it was this—what was it that led a whole generation of British artists who in the 1930s were hovering on the brink of a commitment to abstraction to abandon that route, and retreat into Englishness?

It was not, I think, a failure of nerve that led artists such as Paul Nash or John Piper to turn their backs on abstraction. It was, rather, a stiffening of resolve in the face of the acutely perceived threat to the entire British way of life, as war with Nazi Germany loomed.

WWI—the war I still think of as The Great War—was the great fracture point of recent western history. After it, many artists were only too keen to embrace modernism, and to break with the safe rules of the past. In Britain, this was true only up to a point. When asked why he was fighting in WWI, the poet Edward Thomas picked up a handful of English earth and let it trickle through his fingers: “Literally for this,” he said. I think that visual artists in the 1930s had much the same visceral need to record the British landscape and to define and describe an essential sense of Englishness. Eric Ravilious showed us the English as a nation of shopkeepers in High Street in 1938; Edward Ardizzone explored the life of that most traditional English institution, the pub, in The Local in 1939; in 1944 John Piper fell headily in love with English, Scottish, and Welsh Landscape.

Eric Ravilious, Baker and Confectioner

Lithograph, 1938

Edward Ardizonne, Public Bar at the George

Lithograph, 1940

John Piper, Talland Church, Cornwall

Lithograph, 1944

Of course not every British artist reneged on the modernist agenda—some, such as Ben Nicholson, kept the faith. But most British art of the mid-century was content to idle in a backwater, rather than ride the main current of art history. I can’t bring myself to regret this—because it is a deliciously evocative and enjoyable backwater.

This preamble brings me to the answer to my quiz question, and the true subject of today’s post. If I were faced with that intriguing abstract engraving, with its subtle balance between movement and stillness, and asked to hazard a guess as to its author, I suppose I would think of artists such as Stanley Hayter or Edward Wadsworth. It would have to be a master of the technique, for to engrave such perfect concentric circles with a burin, which is designed to plough a straight furrow, shows immense skill. I would never ever think of the correct name.

Edward Bawden, Abstract design for "Signature"

Copper engraving, 1937

Edward Bawden? I’ve admired and enjoyed Bawden’s art—watercolours, lithographs, linocuts—most of my life, but I never imagined he had ever worked anywhere near the cutting edge of art. Yet here he is, incising a route-map to modernity. But just like John Piper, Bawden never followed this route to its true destination. Instead, he veered off, to create a unique and beautiful body of work that is nevertheless parochial in its appeal. How many of my readers outside Great Britain are familiar with his work? I suspect rather few. So here is a brief tour of Bawden’s art, as exemplified by my own limited collection. The most crucial limitation is that I do not possess any work by Bawden in the medium he made so brilliantly his own, the coloured linocut.

For more serious research, I recommend Malcolm Yorke, Edward Bawden and His Circle (Antique Collectors’ Club, 2007), Jeremy Greenwood, Edward Bawden: Editioned Prints (The Wood Lea Press, 2005), Brian Webb, Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious: Design (Antique Collectors’ Club, 2005), and Oliver Green and Alan Powers, Away We Go: Advertising London’s Transport: Edward Bawden & Eric Ravilious (Mainstone Press, 2006). Malcolm Yorke’s book in particular is the source of much of the information in this post.

That two of those titles couple the name of Edward Bawden with that of Eric Ravilious is no accident. The two met as students at the Royal College of Art (where Paul Nash was one of their teachers) and became close friends and collaborators. Both were official war artists in WWII. Ravilious died, Bawden survived, and outlived his friend by 47 years.

Bawden was born in 1903 in Braintree, Essex. He entered the Department of Industrial Design at the Royal College of Art in 1922. Fellow students at the RCA included Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Barnett Freedman, and Enid Marx. But the most important to Bawden were Eric Ravilious and Douglas Percy Bliss; al three entered the college on the same day. The three friends also shared their first exhibition, at the St George’s Gallery in Bond Street in 1927. Bawden’s 29 works included six copper engravings. Denied entry to the engraving class at the RCA, Bawden too lessons with a commercial engraver, H. K. Wolfenden, at the Sir John Cass Institute. Jeremy Greenwod quotes Bawden as saying, “I became interested in the difficulties of engraving on copper & fascinated by the engraved designs of J. E. Laboureur.”

In 1925, Bawden and Ravilious took lodgings at Brick House, Great Bardfield, Essex. When Bawden married the painter and potter Charlotte Epton in 1932, his father bought Brick House for them as a wedding present; Eric and Tirzah Ravilious lodged with them, and Edward and Eric worked side by side. Edward Bawden was to live at Brick House until 1970, when, widowed, he moved to nearby Saffron Walden. In the postwar years other artists clustered around him. Although a loose affiliation of neighbours and kindred spirits rather than a coherent artistic movement, they have become known as the Great Bardfield Artists, achieving national renown with their pioneering “open studio” events. Just as with Ravilious, there was an edge of rivalry in Bawden’s relations with these fellow artists, notably with Michael Rothenstein. As Michael Yorke writes, Rothenstein, who had been inspired by a visit to S. W. Hayter’s Atelier 17, “saw himself as more ‘advanced’ than the others, a player in an international arena rather than a rural backwater.” This would certainly have got on Bawden’s nerves.

Edward Bawden, The Produce Shop

Lithograph, 1946

Edward Bawden, Village Show

Lithograph, 1946

Edward Bawden, Chapel

Lithograph, 1946

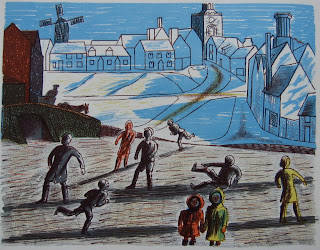

Edward Bawden, Children Skating

Lithograph, 1946

The four colour lithographs above were done to accompany an article by Denis Saurat on “Edward Bawden’s England” in issue 2 of Alphabet and Image, edited by Robert Harling (who himself was to write an early monograph on Bawden’s work). “Without a doubt,” writes Saurat, “Edward Bawden’s England will remain.” The lithographs take up half the page, with text below, and another lithograph on the reverse. They were printed at the Shenval Press.

Edward Bawden, St Mary the Virgin

Lithograph, 1949

Edward Bawden, The Cabinet-Maker

Lithograph, 1949

Edward Bawden, The Bell

Lithograph, 1949

Edward Bawden, The Market Gardener

Lithograph, 1949

The following year, Bawden published Life in an English Village, 16 lithographs with a text by Noel Carrington, in the King Penguin series edited by Nikolaus Pevsner. In Malcolm Yorke’s words, this commission had the advantage for Bawden that “he didn’t even have to stir from Great Bardfield”. As with the images for “Edward Bawden’s England”, the lithographs were printed back-to-back. For this project I have, besides a copy of the book, two interesting sets of proofs. The first comprises proof copies of all 16 lithographs, printed one side of the sheet only, and used by the publisher to make a mock-up layout of the finished book. The second is a signature with the first 8 lithographs, printed back to back, with a few correction marks and an ink stamp on the front, “Passed for Press”. The lithographs were printed at the Curwen Press.

Edward Bawden, The Delinquent Travellers

Lithograph, 1946

Edward Bawden, Medina

Lithograph, 1946

Edward Bawden, China

Lithograph, 1946

Edward Bawden, The desert

Lithograph, 1946

His experiences as a war artist had, paradoxically, ensured that this archetypal Englishman was in fact one of the most widely travelled Englishman of his day—a man familiar with the Marsh Arabs of Iraq, at home across the Middle East. It was this that led to a number of “exotic” commissions, far from the introverted life of the English village. In 1946, Bawden seemed the obvious choice, for instance, to illustrate a choice of Travellers’ Verse in the series New Excursions into English Poetry published by Frederick Muller. Each volume of this series was illustrated with original lithographs by artists such as John Piper (see the plate from English, Scottish, and Welsh Landscape above), John Craxton, Michael Ayrton, and William Scott. The jacket blurb noted that, as a War Artist, Bawden “has never stopped travelling for the last five years in France, in Abyssinia, in Iraq, in Persia and in Italy.” His lithographs for this project were printed by Curwen.

Edward Bawden, The Kaaba at Mecca

Lihtograph, 1949

Edward Bawden, The Battle of Qadisya

Lithograph, 1949

Another project to draw on Bawden’s war work was The Arabs, commissioned by Noel Carrington for Puffin Picture Books, and autolithographed at the Curwen Press. Malcolm Yorke writes of the two double-page spreads, “Both are examples of Bawden’s mastery of the high viewpoint and panoramic sweep combined with tiny details and the deliberate contract of realistic drawing and abstract colour.”

Edward Bawden, Ninth caliph of the Abasside line

Lithograph, 1958

Edward Bawden, She flung him bodily over her shoulder

Lithograph, 1958

Edward Bawden, Great flaming torches... in crevices in the rocks

Lithograph, 1958

Edward Bawden, A good genie appeared in the shape of a shepherd

Lithograph, 1958

My final example of Edward Bawden’s work is a set of colour lithographs made for an edition of Beckford’s Vathek published by The Folio Society in 1958. These are bold and bright, with a graphic strength that draws on Bawden’s linocut work, but I don’t feel the text really suited his temperament, or that the lithographs stand up to those made by Marion Dorn 30 years earlier.

Edward Bawden, The Vicar

Lithograph, 1949

Edward Bawden died at the age of 86 on 21st November 1989, “after a morning spent doing a linocut”. There are two major archives of Edward Bawden’s work: at the Cecil Higgins Art Gallery in Bedford, and at the Fry Art Gallery in Saffron Walden, which is devoted to the work of the Great Bardfield Artists. Malcolm Yorke’s book concludes with the following quote from J. R. Taylor’s review in The Times of Edward Bawden’s last exhibition, in 1989. I shall close this post the same way, for Taylor too touches on the central question of the “Englishness” of Bawden’s art: “Perhaps because this is an English manner of going about art, we suppose that lightness of effect is incompatible with essential seriousness. If Bawden were French, now, we would have more notion of how to appreciate his unique combination of intelligence and fun, true emotion and light lyric grace. Bawden remains unclassifiable, and therefore impossible to estimate. Which is probably just the way he wants it.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)