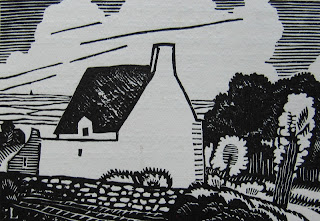

Walter Pach, New York

Etching, 1928

The first is by Walter Pach. The painter, etcher and art critic Walter Pach was born in New York City in 1883. Pach studied under Robert Henri and William Merritt Chase. Moving to Paris, he became part of the artistic and literary circle of Gertrude and Leo Stein. Walter Pach's achievements as an artist have been overshadowed by his enormous influence on American taste in his championing of such artists as Cézanne, van Gogh, and Diego Rivera, as well as Native American art. He was, in effect, the American version of Roger Fry, whose daring choice of art for two groundbreaking Post-Impressionist exhibitions in London in 1910 and 1912 had such a profound affect on British art of the twentieth century. In a similar vein, it was Walter Pach who (with Arthur B. Davies and Walter Kuhn at the Association of American Painters and Sculptors) organised the famous Armory Show of 1913, which is credited with decisively turning American artists towards modernism. Of the organisers, it was the Paris-based Walter Pach who had access to avant-garde artists such as the three brothers Marcel Duchamp, Jacques Villon, and Raymond Duchamp-Villon, whose work caused such as stir when exhibited in the Armory Show (or as it was billed, The International Exhibition of Modern Art). As an artist, Walter Pach was welcomed into the Paris art world, and the publication of this etching accompanied an appreciate essay on his art by Léon Rosenthal. Pach was also elected a member of the Société des Artistes Indépendants. For all his promotion of the avant-garde, on the evidence of this etching Pach did not himself stray far from a Post-Impressionist aesthetic. He died in 1958.

Adriaan Lubbers, The El at Chatham Square

Lithograph, 1930

The second is by the itinerant Dutch artist Adriaan Lubbers. Adriaan Lubbers was born in Amsterdam in 1892. Lubbers is particularly remembered for his paintings, drawings, and lithographs of 1920s New York, which remain one of the most evocative visual records of the city at this vibrant period. His lithograph of the elevated railway (the El, or as Byblis spells it, Le L à Chatham Square), shows a more striking modernism than Pach's. His understanding of the angles and spaces of the city has been radically affected by exposure to Cubism, Vorticism, and Futurism. This is the second of two versions of the same scene; the first, published in 1929, is on a larger scale, but otherwise the two are virtually identical. The second version was made especially for Byblis, to accompany an essay on Lubbers by Charles Terrasse. After living and travelling throughout Europe, Adriaan Lubbers was fittingly in Manhattan when he died of a stroke in 1954.