The art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel was born in Paris in 1831. In 1865 he took over his father’s picture-dealing business, which specialised in the work of the plein-air Barbizon School. Paul Durand-Ruel continued to support the Barbizon artists, but from the early 1870s, sensing a change in the air, he also cultivated a younger set of painters, influenced by Barbizon but going way beyond it in the freedom of their brushstrokes, the Impressionists. Durand-Ruel represented Degas, Manet, Monet, Morisot, Pissarro, Renoir, Sisley, and Guillaumin among others, dominating the art market from his galleries in Paris, London, and New York. He established a new pattern of the gallerist as patron, the maker and breaker of careers, and manipulator of the market.

The 1892 book

L’Art impressioniste d’après la collection privée de M. Durand-Ruel is a record of the Impressionist works that Durand-Ruel kept for himself. The whole book can be read online

here .

It was written by Georges Lecomte, and the publisher on the title page is Typographie Chamerot et Renouard. I assume that the book was commissioned and financed by Durand-Ruel himself. I suspect that even though it is described as his private collection, these works would have been for sale to the right buyer; Durand-Ruel had used a similar tactic in 1873 when he published a partwork with etchings after 300 works he had in stock (mostly Barbizon, with some early Impressionist), entitled

Galerie Durand-Ruel; recueil d'estampes gravées à l'eau-forte.

The main interest of

L’Art impressioniste now lies not in the rather superficial text but in the 35 etchings after paintings in Durand-Ruel’s collection. These etchings were made by the painter, lithographer and etcher Auguste Marie Lauzet. Among many delights, they include 8 etchings after works by Claude Monet, about half of the total number of lifetime etchings after Monet, according to my reckoning. Monet himself never made a single print, so far as I am aware, though he did hand-sign the 20 lithographs made after his paintings by William Thornley in 1890, each published in an edition of only 25 copies.

Auguste Marie Lauzet was born in 1865. He was a close friend of Puvis de Chavannes, and made lithographs after the work of Puvis and Monticelli. These were published by Theo van Gogh at Goupil, and Lauzet was on friendly terms with both Theo and Vincent; he was one of the few mourners at Vincent van Gogh's funeral. The esteem in which Lauzet was held by the artists whose work he interpreted in etching is shown by the way they came to his aid when he fell ill in 1895. A sale was held at the Hotel Drouot on 9 May 1895 of

Tableaux, Aquarelles et Dessins, Scultures, offerts par les Artistes à M. Lauzet. Monet, Degas, and Puvis de Chavannes were among those who donated canvases, and the catalogue stretches to 16 pages. The poet Mallarmé helped Lauzet’s lover, the Symbolist artist Jeanne Jacquemin, organise the sale, writing for instance to Whistler to solicit a contribution (Whistler sent an etching). Despite this help and support, Auguste Lauzet died in 1898, at the age of just 32 or 33.

The etchings Auguste Lauzet made for

L’Art impressioniste d’après la collection privée de M. Durand-Ruel are his most important work as an etcher. I present them here, grouped alphabetically by artist, with minimal commentary. All works are etchings or drypoints by Lauzet, all published in 1892, and all printed on cream laid paper, in various shades of ink: various browns, some in black, some in sanguine, one in a blue-grey. I’ve tried to trace where these paintings currently reside, but have had mixed luck; any help from my readers will be much welcomed.

Eugène Boudin, Le Port de Trouville

(Sold by Durand-Ruel in 1899, now in a private collection)

John Lewis Brown, Chevaux de course

(Current whereabouts unknown to me)

Mary Cassatt, Jeune mère

(Now known as A Caress; New Britain Museum of American Art)

Mary Cassatt, Mère et enfant

(Current whereabouts unknown to me)

Edgar Degas, Chevaux au pâturage

(Current whereabouts unknown to me)

Edgar Degas, Avant la course

(Private collection)

Edgar Degas, Ballet de Don Juan

(Current whereabouts unknown to me)

Edgar Degas, Danseuse

(Current whereabouts unknown to me)

Jean-Louis Forain, Aux Folies-Bergère

(Marlene and Spencer Hays Collection, Nashville)

Stanislas Lépine, L’Esplanade des Invalides

(Sold at Sotheby’s, Paris, in 2008; presumably now in a private collection)

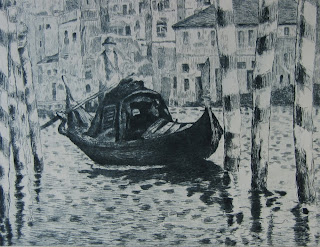

Édouard Manet, Venise

(Now known as The Grand Canal, Venice (Blue Venice); Shelburne Museum, Vermont)

Édouard Manet, Danseurs espagnols

(Now known as Spanish Ballet; the Phillips Collection, Washington)

Édouard Manet, La Femme à la guitar

(Sold by Durand-Ruel in 1894. Now known as The Guitar Player; Hill-Stead Museum, Farmington)

Claude Monet, Cabane de douanier à Pourville

(A drawing with practically the same name, Cabane de douanier près de Pourville, and a very similar look, was sold at Sotheby’s New York in 2000, but I suspect this etching is after one of the various paintings in the Cabane des douaniers series, for which the drawing was a preparatory study)

Claude Monet, Champ de tulips en Hollande

(This is not the same painting as the Field of Tulips in Holland in the Musée d’Orsay, though presumably done at the same time, in the spring of 1886)

Claude Monet, Paysage à Antibes

(Current whereabouts unknown to me)

Claude Monet, Promenade, temps gris

(Now known as Morning at Antibes; Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Claude Monet, Rochers de Belle-Isle

(Musée des Beaux-Arts, Reims)

Claude Monet, Vue d’Antibes

(Now known as Antibes, Afternoon effect; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Claude Monet, Meules à Giverny

(I think this is probably Meules, grand soleil; Hill-Stead Museum, Farmington; but Monet made many paintings of these two particular haystacks, so as always, I may be wrong)

Claude Monet, Église de Varangeville

(Now known as Église de Varangeville, soleil couchant; Private collection, I think)

Camille Pissarro, Sydenham

(Now known as The Avenue, Sydenham; National Gallery, London)

Camille Pissarro, Vue de Rouen

(Now known as Une vue de Rouen depuis cours la Reine; current whereabouts unknown to me)

Camille Pissarro, La Veillée

(Current whereabouts unknown to me)

Camille Pissarro, Retour des champs

(Current whereabouts unknown to me)

Pierre-Cécile Puvis de Chavannes, La Fileuse

(Current whereabouts unknown to me)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, La Femme au chat

(Current whereabouts unknown to me)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, La Terrasse

(Now known as The Two Sisters (On the Terrace); Art Institute of Chicago)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, La Femme à l’éventail

(Hermitage Museum)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pêcheurs au bord de la mer

(Current whereabouts unknown to me)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Déjeuner à Bougival

(Now known as Luncheon of the Boating Party; Phillips Collection, Washington)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, La Loge

(Now known as At the Concert; Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Portrait

(Now known as The Daughters of Paul Durand-Ruel; Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk))

Alfred Sisley, Paysage à Louveciennes

(Current whereabouts unknown to me)

Alfred Sisley, La Seine à Moret

(Current whereabouts unknown to me)

By the time he died in 1922, Paul Durand-Ruel had established Impressionism as the key modern art movement, but it took fifty years of steadfast support, and the taking of breathtaking financial risks, to do so. Without him, life for the Impressionist artists would have been much harder; I feel there is a real historical importance to the Lauzet etchings as a record of which paintings, by which artists, he attached personal importance to. At a glance you can see that for Durand-Ruel the key Impressionists were Monet, Pissarro, Renoir and Degas, with Manet included in the group by default, even though he never exhibited with them. Sisley seems a bit of an afterthought, with only two works illustrated. There’s nothing by Guillaumin, nothing by Cézanne, and of the female Impressionists just two works by Cassatt, with nothing by Morisot, Gonzalès, or Marie Bracquemond.

The balance has shifted somewhat from 1873 when Durand-Ruel published his

Receuil d’estampes. In this, the three younger artists who are championed—anointed, as it were, as the leaders of the new art—are Monet, Sisley, and Pissarro. In the introduction by the critic Armand Silvestre, Monet is picked out as “le plus habile et le plus osé”, the ablest and the most daring of the group. The year before the First Impressionist Exhibition, Durand-Ruel is already promoting these three artists as important innovators, and Silvestre is already writing about their art with real insight and sensitivity. In Monet's handling of water, for instance, Silvestre particularly admires the way “des tons métalliques dus au poli du flot qui clapote par petites surfaces unies miroitent sur ses toiles”—the metallic tones of the shimmering flow, lapping in small discrete surfaces [i.e. blocks of colour, or brushstrokes], sparkle on his canvases. Here is Impressionism described before the term was coined, and described with wholehearted approval. Silvestre loves the way their paintings are flooded with light, and the way they evoke beloved landscapes rather than describe them. I’ve argued before, in my post on

Armand Guillaumin, that critical reaction to the art of the Impressionists was by no means as uniformly negative as is usually assumed; Armand Silvestre’s tender appreciation of the art of Monet, Sisley, and Pissarro is another example of a sympathetic response to the Impressionist aesthetic.

There is an interesting and refreshingly jargon-free thesis on Durand-Ruel and the Impressionists by Marci Regan

here for those who want to know more.