Charles Cottet, Pays de la mer: soir orageux

Lithograph, 1897

Although Cottet too attended classes at the Académie Julian, he is not usually counted even as a member of the Nabis (though he did take up lithography at their urging, contributing his first lithograph to La Revue Blanche in 1894). Instead he is regarded as the leader of the second movement influenced by Pont-Aven, La Bande Noire, or Les Nubians. As the name La Bande Noire suggests, this group, looking back to Gustave Courbet for their inspiration, painted in sombre colours. Whereas the Nabis carried Gauguin’s artistic innovations forward, the Nubians devoted themselves to the subjects that had inspired his art in Pont-Aven—the Breton landscape and the daily lives of the Breton peasants and fisherfolk.

Charles Cottet, Marine

Drypoint, 1906

In the wake of Barbizon artists such as Millet, peasant life was now an accepted subject for art, and one that allowed the artist, in dignifying the toil and hardship of the poor, to offer a subtle critique of the established social order. The Newlyn School in Cornwall, the Danish Impressionists in Skagen, and the Hague School in Holland, all followed Millet’s lead in their choice of subject matter, as did Gauguin’s key artistic ally, Vincent van Gogh.

Charles Cottet, Au pays de la mer: douleur

Etching, 1908

Charles Cottet’s little band of Nubians have been overlooked by art historians, and are long overdue for re-evaluation. Cottet himself was born in Le Puy-en-Velay (Haute-Loire). Although he studied under Puvis de Chavannes and Alfred Roll, even as a student Cottet preferred to work directly from nature rather than under instruction in an atelier. Cottet exhibited at the Impressionist exhibitions organised by Leparc de Bouteville, and exhibited for the first time at the Salon de Paris in 1889. His 65 etchings were all made between 1903 and 1911 when, increasingly disabled by illness, Cottet ceased to etch. In 1906 he was co-opted as a member of the Société des Peintres Graveurs Français, at the invitation of its president, Léonce Bénédit, who was Cottet's friend and patron throughout his career.

Charles Cottet, Bretonne

Etching, 1911

Cottet was one of the founder members of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, and in 1900 of La Société Nouvelle; he also exhibited with the Salon de la Gravure Originale en Couleurs. Although he travelled to Algeria and Egypt, he was most truly at home with the melancholy landscapes of Brittany. Bénézit calls him "un des artistes les plus intéressants du XIXe siècle". Cottet was represented in the 1973 exhibition Visionnaires et Intimistes à l'époque 1900 at the Grand Palais, Paris. There was an exhibition of his work at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Quimper and the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire de Fribourg in 1984, but the art of Charles Cottet is still waiting for a full re-appraisal. The last major retrospective was in 1911, when 431 works were shown at the Galerie Georges Petit. Cottet's graphic work, however, has been fully assessed, with an exhibition at the Musée de Pont-Aven in 2003, and an accompanying Catalogue raisonné de l'oeuvre gravé by Daniel Morane. I am indebted to this work for a number of details in this post.

Charles Cottet, Vieille femme d’Ouessant

Etching and acquatint, published 1922

Cottet’s two most prominent followers were André Dauchez (1870-1948) and Lucien Simon (1861-1945). Dauchez and Simon were not only firm friends and artistic colleagues, but also brothers-in-law.

André Dauchez, La récolte du varech

Etching, 1906

The self-taught painter and printmaker André Dauchez was born in Paris. Dauchez studied printmaking with Gaston Rodriguez; his first prints date from 1887, and his output includes lithographs, etchings, and wood engravings. The Breton landscape was an inexhaustible source of inspiration for Dauchez.

André Dauchez, La chapelle de Beuzec

Etching, 1906

As a painter, André Dauchez exhibited with the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts from 1894, becoming a member of the Society in 1896, its secretary in 1927, and its president in 1938.

André Dauchez, Au-dessus du port de Douarnenez

Etching, 1923

Lucien Simon was also born in Paris. Simon taught at the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts; among his pupils were Lucien Fontanarosa, Yves Brayer, and Georges Rohner. Lucien Simon was himself taught by William Adolphe Bouguereau and Tony Robert-Fleury.

Lucien Simon, Les Marguilliers

Lithograph, 1897

Lucien Simon exhibited regularly at the Salon des Artistes Français; from 1931-1934 he also exhibited at the Royal Academy in London. He specialised in Breton and religious subjects.

Lucien Simon, Causerie du soir

Etching, 1902

One of Cottet's closest allies was René Ménard (1862-1930). Marie Auguste Émile René Ménard was born in Paris, into an artistic family - his father René Joseph Ménard and uncle Louis Nicolas Ménard were both noted painters. He first exhibited at the Salon des Artistes Français in 1883.

René Ménard, Automne

Lithograph, 1897

Another member of La Bande Noire was René François Xavier Prinet (1861-1946). Like Lucien Simon and René Ménard, Prinet was a contributor to the Art Nouveau/Symbolist lithographic portfolios L'Estampe moderne. Prinet was born in Vitry-le-François (Marne). He studied under Gérôme, Courtois and Dagnan-Bouveret. With Albert Besnard, Bourdelle, and Edmond Aman-Jean, Xavier Prinet founded the Salon des Tuileries. Prinet taught many pupils, first at his open studio in Montparnasse, and then at the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts, where he ran an atelier specifically for female students.

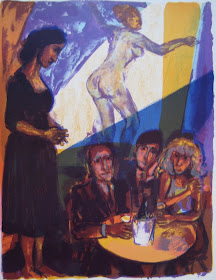

Xavier Prinet, Manon

Lithograph, 1898

A younger artist associated with this group was the Breton painter Jean Julien Lemordant (1882-1968), about whom I have posted before. Lemordant was close to Cottet, and influenced both by Gauguin and the School of Pont-Aven and by the Fauves. Lemordant was blinded at the battle of Artois in October 1915.

Julien Lemordant, Dans le vent

Etching, 1914

You could write a Catalogue Raisonné of Julien Lemordant’s etchings on the back of a postcard: he only made three, all marked by the extraordinary vigour with which he attacked the etching plate.

Julien Lemordant, Ramasseurs de goëmon

Etching, published 1919

Since I first posted about Lemordant I have acquired proofs of his two very Bande Noire etchings of Breton fisherfolk (including one of seaweed gatherers that makes an interesting comparison with an etching of the same subject by Dauchez; both “varech” and “goëmon” mean seaweed). In the interests of completeness, I am re-posting his etching Maisons en construction, which shows his art taking off in a Modernist direction.

Julien Lemordant, Maisons en construction

Etching, 1912