Photograph of Walter Spitzer from the cover of Sauvé par le dessin

A burnt stick and an empty cement bag – with these pitiful materials, Walter Spitzer made his first real drawings, in the Buchenwald concentration camp. It was, as the title of his harrowing memoir Sauvé par le dessin – Buchenwald (Favre, 2004), suggests, his talent for drawing that saved him. Destined one day for one of the “transports” to a satellite death camp, the 16-year-old artist was protected by the internal resistance (who styled themselves the Comité international de résistance aux Nazis) in return for his promise “to engrave in my memory the daily horror, to draw and draw again, to snatch up images from time in order to recall one day in front of the whole world what was happening here.”

Concentration camp, 1965

Lithograph for La Mort dans l'Âme by Jean-Paul Sartre

Spitzer has been true to his word, in paintings, etchings, and in two important sculptures. The first is his bronze Muselman, which won an international competition in 1992 for a monument to the 10,000 Jews murdered in Buchenwald. This was obviously an intensely personal project for Spitzer, who also had a retrospective of 50 years of work at the Buchenwald museum in 1995 to celebrate the presentation of the Muselman statue and the 50th anniversary of the liberation of the camp. A muselman was a prisoner condemned to die because they were too weak to work. Spitzer’s second major sculpture commemorating the Shoah is his Monument du Vel’ d’Hiv’, erected in 1994 in memory of the 12,884 French Jews rounded up by the French police and deported to extermination camps from the Vel’ d’Hiv’ in 1942. In 2000 a documentary, The Art of Survival, was made about Walter Spitzer’s story, but unfortunately I have never seen it.

Hitler, 1965

Lithograph for Le Sursis by Jean-Paul Sartre

Nazis in the street, 1965

Lithograph for Le Mur by Jean-Paul Sartre

Degenerate art, 1965

Lithograph for La Mort dans l'Âme by Jean-Paul Sartre

Born in 1927 in Cieszyn, Poland, Spitzer did survive the camps, and since WWII has lived and worked in France. He studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and forged a successful career as a painter and printmaker. There is a substantial book on his work, Walter Spitzer (Fragments, 2002), with a preface by Elie Wiesel and texts by Daniel Sibony, Youri, Walter J. Strachan, Emmanuel Hayman, and Joseph Kessel. I’ve also consulted Walter Spitzer, la symphonie philosophale de la peinture (Artspectives, 1982).

Prisoners of war, 1960

Lithograph for the Oeuvre romanesque of André Malraux

Soldiers and a woman, 1965

Lithograph for La Mort dans l'Âme by Jean-Paul Sartre

In 1951 Spitzer suffered a catastrophic studio fire which destroyed all his work since 1945. All he saved were two paintings, and the portfolio containing the drawings he had made in Buchenwald; this portfolio then went to the Museum of Israel, to keep it safe from any future conflagrations.

Woman with a water jar, 1960

Lithograph for the Oeuvre romanesque of André Malraux

1957 was the year Spitzer’s fortune changed. In this year he had his first solo show, at the Galerie Monique de Groote in both Paris and Brussels, and also won the Grand Prix des Jeunes Peintures.

Mother and baby, 1965

Lithograph for L'Âge de Raison by Jean-Paul Sartre

Walter Spitzer’s paintings are often on themes from the Torah. Like Marc Chagall, his inspiration wells up constantly from the Old Testament. There are, too, many paintings that evoke the lost world the shtetls.

Ploughing, 1968

Lithograph for L'Odyssée by Nikos Kazantzakis

As a printmaker, Spitzer – often working to illustrate a particular text – reworks his religious themes in human terms. As W. J. Strachan writes in his classic study The Artist and the Book in France, “Spitzer is a notable experimenter in both etching and lithography who yet never ceases to paint and exhibit easel-pictures.”

Pink nude, 1965

Lithograph for L'Âge de Raison by Jean-Paul Sartre

Taken as a whole, the art of Walter Spitzer is concerned with two great, interlinked themes: man’s inhumanity to man, and the humanity of man. Relatively little-known today, he will surely be recognized in the future as one of the great witnesses to the 20th-century experience.

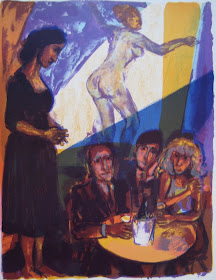

Striptease, 1965

Lithograph for L'Âge de Raison by Jean-Paul Sartre

My prints by Walter Spitzer, lithographs and etchings, derive from limited editions of works by important 20th-century writers – Nikos Kazantzakis, Jean-Paul Sartre, Henry de Montherlant, André Malraux, and his friend Joseph Kessel. In all of these writers the themes of war, peace, grief and compassion are central. In other words, Spitzer was never an illustrator for hire – he accepted invitations to illustrate the work of distinguished writers whose concerns chimed with his own. In the case of Sartre, for instance, Spitzer not only illustrated the collected novels with 64 original lithographs, but also made a whole series of paintings based on the same texts, exhibited at the Galerie Drouant, Paris, in 1966.

Couple by the sea, 1965

Lithograph for Le Sursis by Jean-Paul Sartre

All his important book illustrations are colour lithographs, except for the black-and-white etchings with aquatint for Kessel’s Le Tour du Malheur (La Belle Édition, 1963-64) and the etchings with aquatint for Aucassin and Nicolette (Les Impénitents, 1961).

Joseph Kessel, 1963

Etching for the frontispiece of La Fontaine Medicis by Joseph Kessel

Aucassin and Nicolette was, I believe, Spitzer’s first book commission, for the Bibliophile society Les Impénitents. I haven’t seen a copy of this book (only 126 copies were published), but several are reproduced in Walter Spitzer. Unfortunately the plate W. J. Strachan reproduces as a full-page illustration on p.275 of The Artist and the Book in France, attributed to Aucassin and Nicolette, is in fact one of the etchings from Le Tour du Malheur.

Nude, 1964

Etching for L'Homme de Plâtre by Joseph Kessel

Artists, 1963

Etching for L'Affaire Bernan by Joseph Kessel

Strachan describes the etchings for Le Tour du Malheur (The Tower of Misfortune) as “characteristic of his grimmer mood”. In a preface for the catalogue of Spitzer’s exhibition at the Galerie Romanet in 1963, Joseph Kessel writes that, “I met Walter Spitzer about 2 years ago, when he was illustrating Le Tour du Malheur with etchings as harsh and brilliant as a black diamond.”

Cockerel, 1963

Etching for L'Affaire Bernan by Joseph Kessel

These etchings are perfectly suited to the tone of Joseph Kessel’s autobiographical four-volume novel, which takes us through the life and adventures of Kessel’s alter-ego Richard Dalleau in the First World War and the inter-war years. These etchings seem to me to be a really substantial artistic achievement. There are 41 of them – 32 single and 8 double pages, and they combine pure etching, aquatint, and drypoint with confidence and flair. They show, perhaps more clearly than Spitzer’s colour lithographs, what an incredible draughtsman he is. Spitzer learned his virtuoso etching technique in the atelier of Édouard Goerg. He is a particular master of aquatint.

Orgy, 1964

Etching for Les Lauriers Roses by Joseph Kessel

Horse and cart, 1963

Etching for L'Affaire Bernan by Joseph Kessel

Armistice, 1963

Etching for La Fontaine Medicis by Joseph Kessel

The four volumes of Le Tour du Malheur were published in a surprisingly large edition of 1200 copies, of which 200 were on Arches and 1000 on Lana, plus a further 20 collaborators’ copies. This is quite a substantial print-run for an artist’s book, though there is some doubt in my mind as to whether all these books were actually printed, as at the time of writing there is not a single copy of any of the four volumes being offered for sale. In addition to a set of the books on Lana, I have managed for the first three volumes to additionally acquire one of the 100 suites of the etchings in their first state (printed on Hollande Van Gelder Zonen), and one of the 200 suites of the etchings in their definitive state with remarques (printed on handmade Japon nacré). Sometimes there is a quite extraordinary difference between the first and final states. In the etching The battle, for instance, the first state is a wild explosion of aquatint; in the final state a whole battle scene has been etched on top of this with repeated bitings of the plate and expert use of a drypoint needle. The result is extraordinarly atmostpheric.

The battle (first state), 1963

Etching for La Fontaine Medicis by Joseph Kessel

The battle, 1963

Etching for La Fontaine Medicis by Joseph Kessel

There were also 100 suites of “planches refusées” on Hollande, which I have not managed to see. The etchings were printed quite separately from the text, by the etcher and taille-doucier J.J.J. Rigal.

Opium den, 1964

Etching for Les Lauriers Roses by Joseph Kessel

I first came across Walter Spitzer’s work when I bought one of 450 suites (printed on Arches by Fernand Mourlot) of the lithographs created by Spitzer, Paul Guiramand, André Cottavoz, and André Minaux for a deluxe edition of The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel by Nikos Kazantzakis, published by Éditions Richelieu in 1968. This monumental sequel to Homer’s Odyssey is one of the most remarkable literary achievements of the 20th century. It comprises 33,333 lines of verse, in 24 books. Alternately wonderful and infuriating, it doesn’t make much sense in either Jacqueline Moatti’s French translation or the English version by Kimon Friar. The four French artists evidently felt fairly baffled by this work, and of the 48 lithographs they produced (12 each), most bear only a tangential relationship to the text.

Orgiastic rites at Knossos, 1968

Lithograph for L'Odyssée by Nikos Kazantzakis

Bull-leaping at Knossos, 1968

Lithograph for L'Odyssée by Nikos Kazantzakis

But I was impressed enough to seek out further examples of the work of all four men. In the case of Spitzer, I have added to the Odyssey lithographs one of 695 suites of his lithographs for the Oeuvre Romanesque of Malraux (Éditions Lidis, 1960-1961), one of 500 suites of his lithographs for the Le Chaos et la Nuit and Les Bestiaires by de Montherlant (Éditions Lidis, 1963), and one of 1000 suites of his lithographs for the Oeuvre Romanesque of Jean-Paul Sartre (Éditions Lidis, 1965-1966). All are printed by Mourlot on pure rag Arches. It was Fernand Mourlot himself who recommended Walter Spitzer as the right artist to illustrate the complete fiction of Malraux, which in turn led to the Sartre, Montherlant, Kessel, and Kazantzakis commissions.

Bull's head, 1963

Lithograph for Les Bestiares by Henri de Montherlant

Raging bull, 1960

Lithograph for the Oeuvre romanesque of André Malraux

In 1963 Walter Spitzer exhibited at the Salon des peintres témoins de leur temps at the Musée Galliéra, supplying a lithograph for the accompanying book L’Évènement par Soixante Peintres Témoins de Leur Temps, alongside artists such as Roger Bezombes, Yves Brayer, Jean Carzou, Roger Montané, and Kostia Terechkovitch. Of almost no other artist can it be so literally true that he has been a witness to his time. He himself has said, “I think that is my role, I have to testify.”

Avenging angel, 1965

Lithograph for L'Âge de Raison by Jean-Paul Sartre

The terrible experiences of his youth in the Polish ghetto, in Auschwitz, on the death march to Gross-Rosen, and then in Buchenwald, marked Spitzer for life. He is unflinching in his portrayal of man at his worst; Walter Strachan rightly calls his lithographs for Malraux’s Les Conquerants “violent and tormented”. But in the testimony of his art, Walter Spitzer finds room also for grace notes of redemption, tenderness, and beauty.

Girl with a bouquet, 1965

Lithograph for Le Sursis by Jean-Paul Sartre

a truly touching homage, Neil, i am so grateful to you for being able to learn about such a wonderful artist and person... and i loved your presentation, from the horrors of the camps to that lovely girl in the end, who reminded me a bit of Chagall's powerful grace and innocence...

ReplyDeleteThere's definitely a kinship with Chagall (you can see it in the ploughing picture, too). When Spitzer heard news of Chagall's death, he was working on a large canvas Let My People Go, showing a whole village of Jews leaving their shtetl, clutching their most precious possessions, bound for Israel. As a tribute, Spitzer painted a young Chagall into the picture, holding his brush and palette.

ReplyDeleteLooking at these pictures, it is like a catalogue of all that was destroyed. It seems as if Spitzer tried to summon the people who were gone into his work, to give them an alternate life. I keep returning to "Woman with a water jar", thinking it offers some token of Spitzer's determination. And even if it seems flippant, I like seeing Hitler menaced by Mondrian.

ReplyDeleteI think in many ways Walter Spitzer's entire life's work has been an attempt to use art in an almost magical way to bring back to life what was destroyed.

ReplyDeleteVery powerful Neil, and also very moving. Clive

ReplyDeleteIn the sixties I printed most of the etchings for the illustrated book by W. Spitzer at the J.J.J. Rigal printshop, rue Guerard, Fontenay aux roses.

ReplyDeleteHow interesting, Michel. Thank you so much for taking the time to leave a comment. Atelier J.J.J. Rigal achieved the highest standards in printing etchings, and the name is always a sign of quality.

ReplyDelete