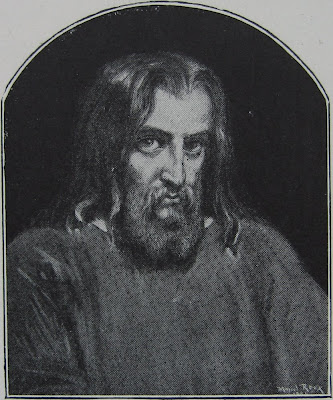

Noël Bureau, Baron Samedi, 1933

Original wood engraving by Noël Bureau (active 1916-1957)

Writing my recent blog entry on Marcel Roux started me thinking about the artistic depiction of personified Death. The skeletal figure of Death was important in western art in the medieval danse macabre, but it isn’t I think until Symbolism that Death really starts dancing again. He continued to do so through Expressionism and Surrealism, right up to the present day, in pieces such as Damien Hirst’s grotesque skull embedded with gemstones.

André Villeboeuf, Danse macabre, 1944

Original etching with aquatint by André Villeboeuf (1893-1956)

One of the interesting things about the various figures of Death in my collection is their fluidity of gender. I think English speakers are probably apt to think of Death as masculine, but Anglo-Saxon had masculine, feminine, and neuter words for death, and in languages such as French, death is a feminine noun, la Mort. The elegant skeletal figure leading the little girl by the hand in Roux’s L’Enfant et la Mort is definitely female. So too is grand Madame la Mort, riding a high-stepping black palfrey in my engraving by Hervé Baille (1896-1974).

Hervé Baille, Madame la Mort, 1945

Original copper engraving

Death figures obsessively in the art of Marcel Roux, featuring in a full third of his etchings. Jean Deville (1901-1972) is another French artist much possessed by death, and my copper engravings by Deville were executed for Sonnets et stances de la Mort by the sixteenth-century metaphysical poet Jean de Sponde, published by Pierre Seghers for the group La Jeune Gravure Contemporaine. Janine Bailly-Herzberg writes of Deville in her Dictionnaire de l’Estampe et France, “Son style, dramatique et quelquefois visionnaire, où la mort est souvent présente et côtoie des personages tourmentés, ne cherche pas à plaire à un grand public.”

Jean Deville, La Mort, 1946

Original copper engraving

Jean Deville was born in Charleville in the Ardennes. He was a pupil of Maurice Denis and Georges Desvallières, and was taught how to etch in 1931 by Yves Alix and Gérard Cochet. From that point, printmaking, especially etching, was crucial to his art. All his prints, including those for Sonnets et stances de la Mort, were printed by Georges Leblanc.

Jean Deville, Et quel bien de la Mort?, 1946

Original copper engraving

Alphonse Legros (1837-1911) is I think the earliest artist in my collection to take Death as a primary subject; perhaps it’s not surprising, given his close friendship with Baudelaire, whose writings on the subject inspired quite a few of the artists whose work will follow in this blog.

Alphonse Legros, Jeune fille et la Mort, 1900

Original wood engraving by Charles de Sousy Ricketts (1866-1931) after a drawing by Alphonse Legros.

Alphonse Legros was a painter, printmaker, and sculptor. Born in Dijon, Legros was apprenticed at the age of 11 to a house painter, who was also a "colourer of images". Legros studied at the Dijon Beaux-Arts, whose director was Célestine Nanteuil, and then at the atelier of Lecoq de Boisbaudran in Paris, where he became close friends with Fantin-Latour. Alphonse Legros moved to England in 1863 and was naturalized in 1880. Legros was encouraged in this move by Whistler, whom he first met in 1858. Although Legros had been one of the most active members of the French Société des Aquafortistes, a close ally of Fantin-Latour and a friend of Charles Baudelaire (for whose translation of Poe had made a series of remarkable etchings), he found it hard to make ends meet in France, and in emigrating to England he was also fleeing his creditors and escaping the threat of debtor's prison. One in London, Legros found himself the neighbour of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the friend of Swinburne, and the centre of admiration among English etchers. His "notoriété Britannique" caused a revision of opinion back in France, and Alphonse Legros had two paintings in the Salon of 1863 and a third - a portrait of his friend Manet - in the Salon des Refusés. Exhibitions at the galleries of Durand-Ruel and Samuel Bing were to follow, and after his hand-to-mouth early years Legros became a popular and successful artist. In London, he was appointed Slade Professor of Art at University College, and professor of etching and engraving at South Kensington.

Alphonse Legros, La Mort et le Bûcheron, 1876

Original etching

Édouard Chimot (1890-1959) has already featured in this blog through his role as art director for Les Éditions d’Art Devambez in the 1920s. My four Chimot etchings on the subject of death all date from just before he joined Devambez. They were made for an edition of the harrowing vision of existential nothingness that is the novel L’Enfer (Hell), by Henri Barbusse. The etchings were printed by Eugène Monnard on Chimot’s own hand-press.

Édouard Chimot, La Mort, 1921

Original etching with aquatint

Édouard Chimot, Ce sont les autres qui meurent, 1921

Original etching with aquatint

Édouard Chimot, L’Enfer, 1921

Original etching with aquatint

Édouard Chimot, Le visage humain, 1921

Original etching with aquatint

An artist working in a similar vein to Chimot at this time was the Russian émigré Serge Ivanoff (1893-1983). Ivanoff was born in Moscow, where is parents enrolled him in the Academy of Art from the age of 10. Following the Russian Revolution the family moved to St. Petersburg, where Ivanoff studied under Braz, the curator of the Hermitage. In 1922 Serge Ivanoff emigrated to France, where he lived and worked for the rest of his life. He became a very successful painter of society portraits, and a member of the staid Salon des Artistes Français. My etchings by Ivanoff show a younger, edgier side to his art. They are illustrations to the classic tale of erotic transgression Les Diaboliques by Barbey d'Aurevilly.

Serge Ivanoff, Death and the maiden, 1925

Original etching

Serge Ivanoff, Death, 1925

Original etching

In the same year as Ivanoff, William Malherbe (1884-1952) was illustrating his brother Henry’s war memoir, La Flamme au Poing. William Malherbe was born in Senlis, Oise. His own experiences in WWI marked him deeply; Time Magazine found him “after four years in the war, almost pathologically shy.”

William Malherbe, Le Divertissement macabre, 1925

Original copper engraving by Achille Ouvré (1872-1951) after a drawing by William Malherbe

William Malherbe’s artistic success came after he was taken up in the 1930 by the gallery Durand-Ruel, whose fortune had been made by its backing of the Impressionists. In 1939, at the age of 55, William Malherbe emigrated to the USA, where he lived on a farm in Vermont until 1948 when he returned to France. His exhibitions at the Corcoran Gallery were highly successful, and his colourful post-Impressionist Vermont scenes, full of light and paint-flecked pleasure, are still highly sought-after. Some even consider William Malherbe an American artist, but his work is essentially rooted in the French post-Impressionist tradition of Bonnard and late Renoir.

David Jones (1895-1974) was, like William Malherbe, deeply marked by his experiences in the trenches in WWI, which he vividly re-imagined in his great long poem In Parenthesis. His copper engravings for an edition of Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner include a classic Death and the Maiden scene, in which the maiden is literally “dicing with death”. It illustrates the point at which a skeleton ship appears:

Are those her ribs through which the Sun

Did peer, as through a gate?

And is that Woman all her crew?

Is that a DEATH? and are there two?

Is DEATH that woman’s mate?

Her lips were red, her looks were free,

Her locks were yellow as gold:

Her skin was white as leprosy,

The Night-mare LIFE-IN-DEATH was she,

Who thicks man’s blood with cold.

The naked hulk alongside came,

And the twain were casting dice;

“The game is done! I’ve won! I’ve won!

Quoth she, and whistles thrice.

David Jones, Life-in-Death, 1929

Original copper engraving

Jones made between 150 and 200 preparatory drawings for this, his last major series of engravings, which he executed in “simple incised lines reinforced here and there and as sparingly as possible by cross-hatched areas… I decided also that these essentially linear designs should have an undertone over the whole area of the plate.” This latter effect was achieved by not wiping the plates totally clean of ink before putting them in the press.

David Jones’ engravings for the Rime contain a lot of submerged Christian imagery, with the Ancient Mariner hanging from the mast like Christ on the cross, and the albatross equated to Christian depictions of the pelican in her piety. In the etching Calvary, executed in the dark days of 1942 by Alméry Lobel-Riche (1877-1950), the artist manages to fuse Christ and Death into one powerful image of desolation and defeat.

Alméry Lobel-Riche, Calvary, 1942

Original etching

In the interests of actually getting this post finished and up on the blog, I think I’ll let the pictures speak for themselves from now on; just ask if you want further information on any of the artists or images.

Hubert Yencesse, Love and Death, 1947

Original wood engraving by Hubert Yencesse (1900-1987)

Jacob Epstein, A Fantastic Engraving, 1940

Original lithograph by Jacob Epstein (1880-1959)

Jacob Epstein, The Two Good Sisters, 1940

Original lithograph

Mariette Lydis, Un cheval de race, 1948

Original etching with aquatint by Mariette Lydis (1887-1970)

Jean Carzou, Death with a flower, 1964

Original lithograph by Jean Carzou (1907-2000)

André Minaux, Skull, 1968

Original lithograph by André Minaux (1923-1986)

Pierre Jacquot, Death, 1980

Original lithograph by Pierre Jacquot (1929- )