This is the first in what I hope will be a series of blogs on neglected women artists. Of course the very term is tautologous: all women artists are neglected. Even those of the very top rank – Sonia Delaunay, Berthe Morisot, Gwen John, Winifred Nicholson – get only a fraction of the attention of male artists of similar stature. But you only have to look a little below the glossy accepted surface of art history to find women artists of real achievement and importance of whom, quite frankly, nobody has ever heard.

Angèle Delasalle is a case in point. She was well enough known in her day – I have essays on her from the Gazette des Beaux-Arts and the Revue de l’art ancien et moderne – and she merits a decent entry in Benézit, but she has been almost completely forgotten.

Angèle Delasalle

Delasalle studied under Jean-Paul Laurens, Jean Benjamin-Constant, and Jules Lefebvre. As an oil painter she specialised in portraits, landscapes, and female nudes, exhibiting at the Salon des Artistes Français from 1894 the Salon de la Société des Beaux-Arts from 1903, and with the Salon d'Automne from its foundation.

Delasalle first came to attention with history paintings, such as Cain and Enoch’s daughters in 1895, and the prize-winning oil Retour de la chasse at the Salon des Artistes Français of 1898; this was bought by the state and is now in the Musée de la ville de Poitiers. In 1899 a travel scholarship enabled her to spend time in Holland and England, where she absorbed the influences of Rembrandt and Turner. A 1902 exhibition at the Grafton Gallery drew from one critic the observation that her views of London were "more English than England herself" ; an etching of 1907, that I have not seen, is entitled simply Enfield.

In his essay “Peintres-graveurs contemporains - Angèle Delasalle” (Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 1 October, 1912), Raymond Escholier lists 28 etchings by Angèle Delasalle, executed between 1904 and 1912. So far as I am aware, this is a complete catalogue of her etched work; I’ve not come across any reference to further etchings. Though they seem to be scarce as hen’s teeth, I’ve managed to acquire proofs of 9 of these etchings, 3 of them in variant printings.

Within those 28 etchings, Delasalle’s work is very varied. The only category I don’t have any example of is her etchings of big cats – tigers, lions, panthers – of which there are 7. The most likely of them to turn up, I guess, is Tigre dévorant sa proie, which was published by the Société des amis de l’eau-forte in 1908.

Wild animals are not a groundbreaking subject for a woman artist of the day, who might be looking back, say, to Rosa Bonheur. The female nude is another matter. Angèle Delasalle was among the first woman artists to take the female nude as one of her prime subjects, and she did so in a way that was immediately recognized as different. As Raymond Escholier wrote of her nude studies, “Ils sont autant des déshabillés que de nus”; they are naked rather than nude. He writes, “She simply paints the woman who is in front of her eyes.”

Delasalle exhibited a number of paintings of nudes, such as Femme à sa toilette at the Salon des Artistes Français in 1910, or Les baigneuses at the same Salon a year later. The best-known of these today is probably her sensually-slumped full-frontal nude Femme endormie, in the Musée d’Orsay. She also made four etchings of female nudes, of which the fourth shares the title of, and is probably an interpretation of, the painting Femme à sa toilette. I have proofs of the other three: Le déjeuner, Étude de nu, and Le repos.

Angèle Delasalle, Le déjeuner, etching, 1907

Le déjeuner, published by the Revue de l’art ancien et moderne in 1907, deliberately disrupts the male gaze by showing the nude model not in a provocative pose but relaxing, enjoying a well-earned break. She is shown from the back, cup and saucer in hand. This is the model as a working girl, not as eye-candy.

Angèle Delasalle, Étude de nu, etching, 1908

Étude de nu, published by the Revue in 1909 (though executed the previous year), is more conventional in its pose. The model is sitting resting her head on her elbow, with her right hand folded across her breast. She has a subtle air of resigned melancholy, “une intimité que l’heure fait un peu tragique” as the critic Raymond Bouyer wrote. Only when you look at the item of furniture she is sitting on do you realise that this bored beauty is another kind of working girl, for she is reclining on the kind of circular sofa found in the salon of a French maison close, or brothel. This subject would have been quite shocking for a female artist of 1909, which no doubt explains the deliberately bland title, Nude Study.

Angèle Delasalle, Le repos, etching, 1909

The third etching, Le repos, published by the Gazette des Beaux-arts, also in 1909, also plays with the taboo of female recognition of the role that prostitution played in French society. The model’s pose is evidently based on Manet’s scandalous Olympia, but where the model’s frank gaze back at the viewer seemed shocking and provocative in Manet, here it seems perfectly natural, even though Delasalle’s model is not, like Manet’s, coyly covering her pudendum with her hand.

Angèle Delasalle, Le couvreur, etching, 1910

This preoccupation with the naked woman as a working woman ties in with another unusual category in the art of Angèle Delasalle, which is paintings, etchings and drawings of men at work. There is a drawing of a miner in the Département des arts graphiques of the Louvre, and a painting entitled La forge in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen. I have two etchings exploring the working life of men, once again uncharted territory for a woman artist. The first, Le couvreur, depicts a roofer standing in a very masculine pose on the ridge of a roof, with Paris spread out below him. Etched in 1910, and published in 1912 by the Gazette des Beaux-Arts, it is based on a painting that Angèle Delasalle exhibited to great acclaim at the Salon des Artistes Français in 1902. Somewhere in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts around this date is a reproduction of a pencil drawing of the same subject. Ironically, considering the scarcity of Delasalle’s work, I have been been able to acquire three proofs of this etching – the standard issue printed in black on wove paper plus two rare variants on japan paper, one in black and one in red-brown.

Angèle Delasalle, Coin de fonderie, etching, 1910

The second study of workmen is a vigorous and dramatic etching of men in a foundry, entitled Coin de fonderie (or Coin de forge, according to Escholier). It was etched in 1910, and published by the Revue de l’art ancien et moderne in 1913, the last date of pubication for any etching of Delasalle that I have encountered. Writing in the Revue, the critic P. Lelarge-Desar compares this etching with an earlier work, L’abside de Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois, from 1905. Superficially there is nothing in common between the violent clamour of a foundry and the stillness and peace of an ancient church, but Lelarge-Desar shows how Angèle Delasalle distils the essence of both subjects into a strong contrast between light and dark, the known and unknown.

Angèle Delasalle, L'abside de Saint-Germain-L'Auxerrois, etching, 1905

In choosing such subjects as the female nude and the working man, Angèle Delasalle was deliberately challenging current views on the appropriate subjects and the appropriate aesthetic values for a woman artist. In an age when women artists were usually praised for feminine virtues of delicacy and subtlety, Raymond Escholier noted in Angèle Delasalle “la virilité de son dessin”, the virility of her line. Raymond Bouyer, writing in the Revue de l’art ancien et moderne in 1911, also writes of her “qualités quasi viriles”. Writing in the Magazine of Art in June 1902 (quoted in Clara Erskine Clement, Women in the Fine Arts, 1904), B. Dufernex notes that, “Her characteristic energy is such that her sex cannot be detected in her work; in fact, she was made the first and only woman member of the International Association of Painters under the impression that her pictures – signed simply A. Delasalle – were the work of a man.” Once having elected her, it appears that the grandiose International Association of Painters had no means of rectifying their mistake.

Angèle Delasalle, Portrait de jeune homme, etching with aquatint, 1908

The same strength and power exhibited in Le couvreur and Coin de fonderie is evident in the Portrait de jeune homme, an etching with drypoint and acquatint. This young man has such presence you wouldn’t be surprised if he just strolled into the room. You certainly see in this etching why Angèle Delasalle became a sought-after portraitist. Perhaps her best-known portraits are that of her teacher Jean Benjamin-Constant, exhibited at the Salon des Artistes Français in 1902 and acquired by the Musée du Luxembourg (now in the Musée d’Orsay), and that of Clémence Royer in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nantes. The choice of the scientist Clémence Royer as a sitter is a telling one. Royer was a self-made woman, a ground-breaking scientist who was the first to introduce Darwin’s theory of evolution to France; she was tellingly praised, in words that echo the backhanded praise of Delasalle herself, as “almost a man of genius”.

Angèle Delasalle, L'allée de Meudon, etching, 1910

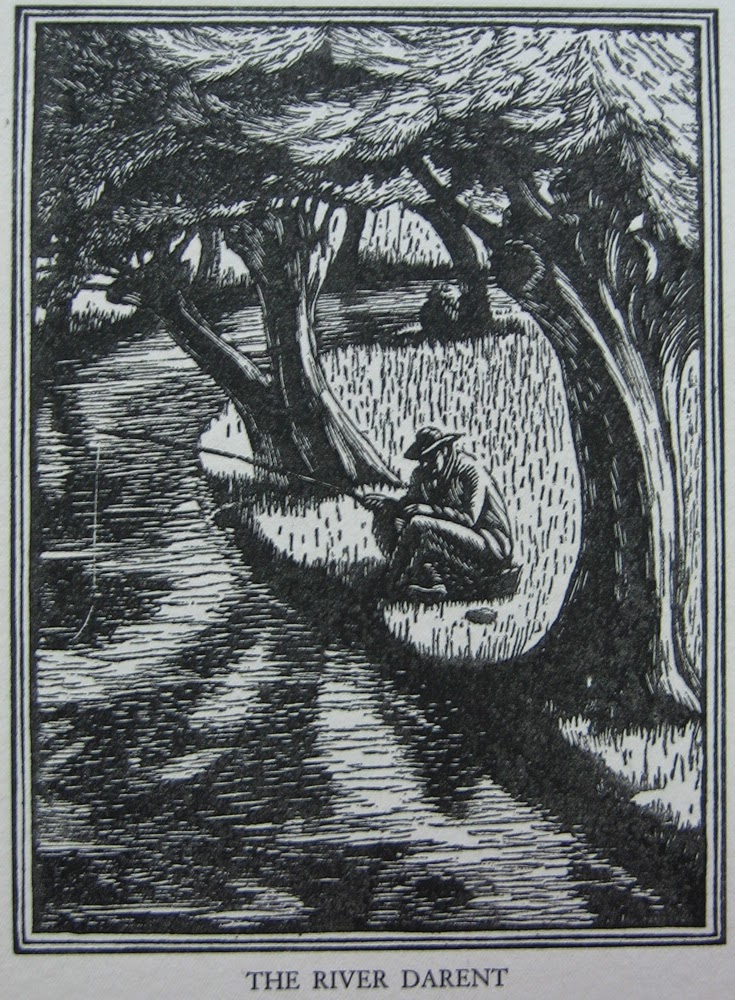

My last two Delasalle etchings are landscapes, The first is a cathedral-like arched walkway of trees, entitled either L’allée de Meudon or L’allée de Bellevue, depending on whether you believe the Revue or the Gazette. The Revue makes a point of the fact that this atmospheric scene was etched on the spot, en plein air, rather than back in the studio from a preliminary drawing.

Angèle Delasalle, À Montigny-Beauchamps, etching, 1911

This direct contact with nature is even more evident in the second landscape, À Montigny-Beauchamps. This, too, looks as if it was drawn directly on the etching plate in front of the motif. Interestingly, in discussing this work Raymond Bouyer leapfrogs back over the Impressionists to the Barbizon School, comparing it to the work of that great pre-Impressionist Paul Huet. I’ve been lucky enough to acquire both the standard issue of this etching on wove paper and one of a very few copies on Japan; when the pre-WWI Revue de l’art ancien et moderne issued de luxe editions of etchings in this way, there were typically 10 proofs on parchment and 30 on Japan.

Angèle Delasalle seems to me to not just an important, and scandalously neglected, woman artist, but an important artist per se. She had an independent eye, a vigorous line, a strong sense of composition, and an ability to convey both the vastness of nature and the intimate reality of a woman’s body, the hush of a church and the hubbub of a foundry. In her own day she won numerous prizes, and in 1926 she was made a Chevalier of the Légion d'Honneur – but in the years that have followed she has never been accorded the honour her art is due, not simply for its ground-breaking confidence but for its scope, its ambition, and its achievement.