Barnett Freedman, Self-portrait at the lithographic stone

Drawing, 1938

Barnett Freedman himself worked very closely with several printers who specialised in printing autolithographs—in particular with Harold Curwen at the Curwen Press, with Thomas Griffits at Vincent Brooks Day and subsequently at Fred Phillips’s Baynard Press, and with the Shenval Press and Chromoworks. He even produced advertising posters for them to demonstrate their skills. While Freedman had very much the mindset of a fine artist, he had the desire to communicate with a mass audience that is more common in the commercial artist. Much of his output was book jackets (mainly for Faber & Faber), posters, or book illustrations (chiefly for George Macy’s Limited Editions Club). Yet his artist peers regarded him not as a jobbing illustrator, but as the finest lithographer of his day, almost certainly the finest Britain had ever seen. Freedman himself refused to make any distinction between commercial and fine art. Pat Gilmour writes in Artists at Curwen (Tate Gallery, 1977): “’What’s commercial art?’ he would ask when the topic was raised. ‘There’s only good art and bad art.’”

Barnett Freedman, Advert for The Curwen Press

Lithograph, 1936

Barnett Freedman, Advert for The Baynard Press

Lithograph, 1938

Barnett Freedman, Advert for Henderson & Spalding at the Sylvan Press

Lithograph, 1939

Barnett Freedman, Advert for Chromoworks

Lithograph. 1950

Freedman took to lithography like a duck to water. What he most valued in the process was the “freedom of expression emanating from the artist’s hand to the printing surface, without any hindrance” (“Autolithography or Substitute Works of Art”).

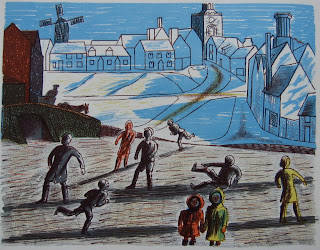

Barnett Freedman, A fine old city

Lithograph for Lavengro, 1936

There is a wonderful book on Barnett Freedman as a lithographer by Ian Rogerson: Barnett Freedman: The Graphic Work, with an essay on Freedman as master lithographer by Michael Twyman (The Fleece Press, 2006). Rogerson quotes Freedman from his essay “Lithography: A Painter’s Excursion” in Signature 2, 1936: it is “the immense range and strength of tonality that can be obtained, the clarity and precision of delicate and fine work and the delightful ease of manipulation by the artist directly on to the stone, plate, transfer paper or celluloid which gives autolithography as supreme advantage over other autographic methods.”

Barnett Freedman, Fair

Lithograph for Lavengro, 1936

Although he lists above various methods of creating lithographs, Barnett Freedman himself always preferred to work directly on to lithographic stone. As Michael Twyman writes, “The lithographic crayon became his main means of making marks, and he relished the sensuous way in which it allowed him to caress the finely-grained surface of lithographic stone.”

The colophon of War and Peace

with Barnett Freedman's signature and thumbprint

The phrase above, “making marks”, is key to understanding Barnett Freedman’s art. He was above all a mark-maker, as he demonstrated when signing the colophon of the Limited Edition Club’s 6-volume edition of War and Peace, which he had illustrated. He did sign his name, as requested, but he also dipped his thumb in red ink and literally “made his mark”.

Barnett Freedman, War and Peace

Lithograph for War and Peace, 1938

Barnett Freedman, Oak Tree

Lithograph for War and Peace, 1938

The lithographs for War and Peace (1938) are generally reckoned to be Barnett Freedman’s masterwork. They were made at the Baynard Press and printed by Thomas Griffits (though neither Baynard nor Griffits get a credit), and show an immense confidence in the confidence of the lithographic stones to convey the subtlest of messages, whether in the deep perspective of a wild troika ride, or in an extreme close-up portrait.

Barnett Freedman, Troika ride

Lithograph for War and Peace, 1938

Barnett Freedman, Pierre

Lithograph for War and Peace, 1938

One interesting change in Freedman’s practice as an illustrator in War and Peace is that he abandons the traditional relationship of the dimensions of the illustrations to the dimensions of the text block. In his lithographs for Lavengro two years earlier, the illustrations exactly match the text, albeit with a couple of rounded corners. But those for War and Peace, and those for Henry the Fourth Part I in 1939 and Anna Karenina in 1951, are long and thin, with a wide margins to the right, a narrower margin to the left and the image bleeding off the page top and bottom. This produces a very striking assymetrical effect across the spread as a whole. He explains this unusual approach in his note on the lithographs for Henry the Fourth in the insert A Shakespeare Commentary that accompanied the book. He writes: “I have attempted to enrich the book, and enhance the beauty of the typography, not by the accepted method of producing an illustration that ‘goes’ with the type, but by an entirely contrasting one. The shape of the picture is in direct contra-distinction to the type-area, as is the colour and general weight, and the method of carrying the whole design through the page, from top to bottom, serves to retain continuity, and has been, I believe, rarely used.” Freedman also tells us that: “The illustrations are auto-lithographs in six printings, drawn on the stones and printed directly from them under my supervision. No photo-mechanical reproduction has been allowed to interfere with my original work, such as it is.” I particularly love that faux-modest “such as it is”!

Barnett Freedman, The Sack of Moscow

Lithograph for War and Peace, 1938

Barnett Freedman, Farm

Lithograph for War and Peace, 1938

Looking through some old copies of the long-running art revue The Studio, I found in the issue for November 1958 an article on Barnett Freedman by Charles S. Spencer. Freedman had died earlier that year, at the age of just 56. Spencer’s article is largely concerned with Freedman as a painter, as it was tied in with the 1958 retrospective of Freedman’s work organized by the Arts Council (the catalogue of which has an introduction by Stephen Tallents), but he also discusses Freedman’s graphic work. He writes, “The unrivalled potentialities of lithography in book publishing were not recognized until Barnett Freedman’s work. He proved the great superiority of auto-lithography over machine processes.”

Barnett Freedman, Falstaff

Lithograph for Henry the Fourth Part I, 1939

Barnett Freedman, The Battlefield

Lithograph for Henry the Fourth Part I, 1939

Spencer draws attention in particular to Barnett Freedman’s lithographs for two projects: Henry the Fourth and Anna Karenina (both projects printed at the Curwen Press). In the lithographs for Henry the Fourth, Spencer notes that “a richness of characterization is allied to warm, subtle colour.” The lithograph of the scene before the battle is singled out as “a remarkable evocation”.

Barnett Freedman, Anna dreaming

Lithograph for Anna Karenina, 1951

Barnett Freedman, Banquet

Lithograph for Anna Karenina, 1951

The lithographs for Anna Karenina are admired for their “Renoir-like delicacy”, and Spencer remarks on a “romantic, rather impressionistic quality” to Freedman’s lithographs as a whole.

Barnett Freedman, Family

Lithograph for Anna Karenina, 1951

I don’t dispute any of the remarks above, but I do believe Freedman’s art is rather more robust than they suggest. His mastery of the long perspective and the sharp close-up and his sure sense of the formal organization of an image are instruments which he uses to convey a wide range of emotion—tenderness, passion, excitement, sorrow, aggression, fear, anticipation, regret. If we forget their function as commissioned book illustrations and simply look at each image as an image (and Freedman himself encouraged this by binding up sets of proofs of these lithographs as gifts for friends), then Freedman’s remarkable range of artistic expression leaps into focus.

Barnett Freedman, Freemason's Lodge

Lithograph for War and Peace, 1938

There is an archive of Barnett Freedman’s work at Manchester Metropolitan University. The initial guide to this collection by Ian Rogerson and Sue Hoskins is entitled Barnett Freedman: Painter, Draughtsman, Lithographer (Manchester Polytechnic Library, 1990). The title is accurate, but it is surely the last word that defines his importance: lithographer.