There was a serious question behind the quiz in my last post, and it was this—what was it that led a whole generation of British artists who in the 1930s were hovering on the brink of a commitment to abstraction to abandon that route, and retreat into Englishness?

It was not, I think, a failure of nerve that led artists such as Paul Nash or John Piper to turn their backs on abstraction. It was, rather, a stiffening of resolve in the face of the acutely perceived threat to the entire British way of life, as war with Nazi Germany loomed.

WWI—the war I still think of as The Great War—was the great fracture point of recent western history. After it, many artists were only too keen to embrace modernism, and to break with the safe rules of the past. In Britain, this was true only up to a point. When asked why he was fighting in WWI, the poet Edward Thomas picked up a handful of English earth and let it trickle through his fingers: “Literally for this,” he said. I think that visual artists in the 1930s had much the same visceral need to record the British landscape and to define and describe an essential sense of Englishness.

Eric Ravilious showed us the English as a nation of shopkeepers in High Street in 1938; Edward Ardizzone explored the life of that most traditional English institution, the pub, in The Local in 1939; in 1944 John Piper fell headily in love with English, Scottish, and Welsh Landscape.

Eric Ravilious, Baker and Confectioner

Lithograph, 1938

Edward Ardizonne, Public Bar at the George

Lithograph, 1940

John Piper, Talland Church, Cornwall

Lithograph, 1944

Of course not every British artist reneged on the modernist agenda—some, such as Ben Nicholson, kept the faith. But most British art of the mid-century was content to idle in a backwater, rather than ride the main current of art history. I can’t bring myself to regret this—because it is a deliciously evocative and enjoyable backwater.

This preamble brings me to the answer to my quiz question, and the true subject of today’s post. If I were faced with that intriguing abstract engraving, with its subtle balance between movement and stillness, and asked to hazard a guess as to its author, I suppose I would think of artists such as Stanley Hayter or Edward Wadsworth. It would have to be a master of the technique, for to engrave such perfect concentric circles with a burin, which is designed to plough a straight furrow, shows immense skill. I would never ever think of the correct name.

Edward Bawden, Abstract design for "Signature"

Copper engraving, 1937

Edward Bawden? I’ve admired and enjoyed Bawden’s art—watercolours, lithographs, linocuts—most of my life, but I never imagined he had ever worked anywhere near the cutting edge of art. Yet here he is, incising a route-map to modernity. But just like John Piper, Bawden never followed this route to its true destination. Instead, he veered off, to create a unique and beautiful body of work that is nevertheless parochial in its appeal. How many of my readers outside Great Britain are familiar with his work? I suspect rather few. So here is a brief tour of Bawden’s art, as exemplified by my own limited collection. The most crucial limitation is that I do not possess any work by Bawden in the medium he made so brilliantly his own, the coloured linocut.

For more serious research, I recommend Malcolm Yorke, Edward Bawden and His Circle (Antique Collectors’ Club, 2007), Jeremy Greenwood, Edward Bawden: Editioned Prints (The Wood Lea Press, 2005), Brian Webb, Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious: Design (Antique Collectors’ Club, 2005), and Oliver Green and Alan Powers, Away We Go: Advertising London’s Transport: Edward Bawden & Eric Ravilious (Mainstone Press, 2006). Malcolm Yorke’s book in particular is the source of much of the information in this post.

That two of those titles couple the name of Edward Bawden with that of Eric Ravilious is no accident. The two met as students at the Royal College of Art (where Paul Nash was one of their teachers) and became close friends and collaborators. Both were official war artists in WWII. Ravilious died, Bawden survived, and outlived his friend by 47 years.

Bawden was born in 1903 in Braintree, Essex. He entered the Department of Industrial Design at the Royal College of Art in 1922. Fellow students at the RCA included Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Barnett Freedman, and Enid Marx. But the most important to Bawden were Eric Ravilious and Douglas Percy Bliss; al three entered the college on the same day. The three friends also shared their first exhibition, at the St George’s Gallery in Bond Street in 1927. Bawden’s 29 works included six copper engravings. Denied entry to the engraving class at the RCA, Bawden too lessons with a commercial engraver, H. K. Wolfenden, at the Sir John Cass Institute. Jeremy Greenwod quotes Bawden as saying, “I became interested in the difficulties of engraving on copper & fascinated by the engraved designs of J. E. Laboureur.”

In 1925, Bawden and Ravilious took lodgings at Brick House,

Great Bardfield, Essex. When Bawden married the painter and potter Charlotte Epton in 1932, his father bought Brick House for them as a wedding present; Eric and Tirzah Ravilious lodged with them, and Edward and Eric worked side by side. Edward Bawden was to live at Brick House until 1970, when, widowed, he moved to nearby Saffron Walden. In the postwar years other artists clustered around him. Although a loose affiliation of neighbours and kindred spirits rather than a coherent artistic movement, they have become known as the Great Bardfield Artists, achieving national renown with their pioneering “open studio” events. Just as with Ravilious, there was an edge of rivalry in Bawden’s relations with these fellow artists, notably with Michael Rothenstein. As Michael Yorke writes, Rothenstein, who had been inspired by a visit to S. W. Hayter’s Atelier 17, “saw himself as more ‘advanced’ than the others, a player in an international arena rather than a rural backwater.” This would certainly have got on Bawden’s nerves.

Edward Bawden, The Produce Shop

Lithograph, 1946

Edward Bawden, Village Show

Lithograph, 1946

Edward Bawden, Chapel

Lithograph, 1946

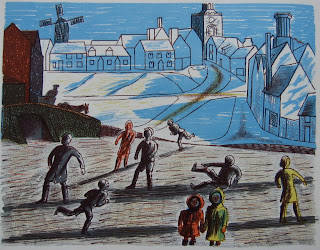

Edward Bawden, Children Skating

Lithograph, 1946

The four colour lithographs above were done to accompany an article by Denis Saurat on “Edward Bawden’s England” in issue 2 of Alphabet and Image, edited by Robert Harling (who himself was to write an early monograph on Bawden’s work). “Without a doubt,” writes Saurat, “Edward Bawden’s England will remain.” The lithographs take up half the page, with text below, and another lithograph on the reverse. They were printed at the Shenval Press.

Edward Bawden, St Mary the Virgin

Lithograph, 1949

Edward Bawden, The Cabinet-Maker

Lithograph, 1949

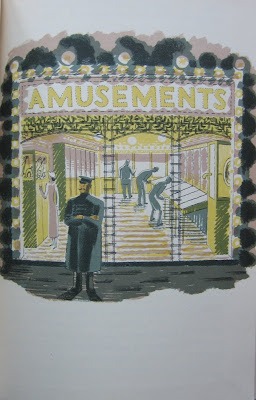

Edward Bawden, The Bell

Lithograph, 1949

Edward Bawden, The Market Gardener

Lithograph, 1949

The following year, Bawden published Life in an English Village, 16 lithographs with a text by Noel Carrington, in the King Penguin series edited by Nikolaus Pevsner. In Malcolm Yorke’s words, this commission had the advantage for Bawden that “he didn’t even have to stir from Great Bardfield”. As with the images for “Edward Bawden’s England”, the lithographs were printed back-to-back. For this project I have, besides a copy of the book, two interesting sets of proofs. The first comprises proof copies of all 16 lithographs, printed one side of the sheet only, and used by the publisher to make a mock-up layout of the finished book. The second is a signature with the first 8 lithographs, printed back to back, with a few correction marks and an ink stamp on the front, “Passed for Press”. The lithographs were printed at the Curwen Press.

Edward Bawden, The Delinquent Travellers

Lithograph, 1946

Edward Bawden, Medina

Lithograph, 1946

Edward Bawden, China

Lithograph, 1946

Edward Bawden, The desert

Lithograph, 1946

His experiences as a war artist had, paradoxically, ensured that this archetypal Englishman was in fact one of the most widely travelled Englishman of his day—a man familiar with the Marsh Arabs of Iraq, at home across the Middle East. It was this that led to a number of “exotic” commissions, far from the introverted life of the English village. In 1946, Bawden seemed the obvious choice, for instance, to illustrate a choice of Travellers’ Verse in the series New Excursions into English Poetry published by Frederick Muller. Each volume of this series was illustrated with original lithographs by artists such as John Piper (see the plate from English, Scottish, and Welsh Landscape above), John Craxton, Michael Ayrton, and William Scott. The jacket blurb noted that, as a War Artist, Bawden “has never stopped travelling for the last five years in France, in Abyssinia, in Iraq, in Persia and in Italy.” His lithographs for this project were printed by Curwen.

Edward Bawden, The Kaaba at Mecca

Lihtograph, 1949

Edward Bawden, The Battle of Qadisya

Lithograph, 1949

Another project to draw on Bawden’s war work was The Arabs, commissioned by Noel Carrington for Puffin Picture Books, and autolithographed at the Curwen Press. Malcolm Yorke writes of the two double-page spreads, “Both are examples of Bawden’s mastery of the high viewpoint and panoramic sweep combined with tiny details and the deliberate contract of realistic drawing and abstract colour.”

Edward Bawden, Ninth caliph of the Abasside line

Lithograph, 1958

Edward Bawden, She flung him bodily over her shoulder

Lithograph, 1958

Edward Bawden, Great flaming torches... in crevices in the rocks

Lithograph, 1958

Edward Bawden, A good genie appeared in the shape of a shepherd

Lithograph, 1958

My final example of Edward Bawden’s work is a set of colour lithographs made for an edition of Beckford’s Vathek published by The Folio Society in 1958. These are bold and bright, with a graphic strength that draws on Bawden’s linocut work, but I don’t feel the text really suited his temperament, or that the lithographs stand up to those made by

Marion Dorn 30 years earlier.

Edward Bawden, The Vicar

Lithograph, 1949

Edward Bawden died at the age of 86 on 21

st November 1989, “after a morning spent doing a linocut”. There are two major archives of Edward Bawden’s work: at the

Cecil Higgins Art Gallery in Bedford, and at the

Fry Art Gallery in Saffron Walden, which is devoted to the work of the Great Bardfield Artists. Malcolm Yorke’s book concludes with the following quote from J. R. Taylor’s review in The Times of Edward Bawden’s last exhibition, in 1989. I shall close this post the same way, for Taylor too touches on the central question of the “Englishness” of Bawden’s art: “Perhaps because this is an English manner of going about art, we suppose that lightness of effect is incompatible with essential seriousness. If Bawden were French, now, we would have more notion of how to appreciate his unique combination of intelligence and fun, true emotion and light lyric grace. Bawden remains unclassifiable, and therefore impossible to estimate. Which is probably just the way he wants it.”