I first came across the work of the etcher Eugène Véder in issue 17 of the art revue Byblis (Spring 1926), which published his etching La rue Saint-Denis. I thought it a lovely piece of work, and was intrigued to find out more about its creator - especially as my copy was hand-signed by the artist. I think Véder probably signed every copy of this print. Usually in Byblis there were 105 hand-signed and 500 unsigned impressions, but in this case there seem to have been 105 in colour and 500 in black-and-white, all signed.

Eugène Véder, La rue Saint-Denis

Etching, 1926

Byblis was published by the art publisher Albert Morancé. Morancé was evidently equally struck by Véder's work, because the Winter 1926 issue of Byblis carries a full-page advertisement for a work to appear the following June from Éditions Albert Morancé:

Paris: 50 Eaux-Fortes originales en couleurs d'Eugène Véder, réunies en un portefeuille d'amateur. There were to be 100 copies on Japon impérial at a subscriber's price of 800 francs, 400 copies on vélin de Rives at a subscription price of 400 francs, and 25 hors commerce copies, 5 on Japon and 20 on Rives. On publication the prices were to rise to 1000 and 500 francs. I believe that 1000 francs then would be about 500 euros today.

Title page of Paris: 50 Eaux-fortes originales

I have managed to find a copy of this exceptionally rare work. It is one of the 20 hors commerce copies on B.F.K. Rives. It consists simply of 50 loose etchings with a title page and a contents page, in a paper cover. Remarkably, it still looks in brand-new, perfect condition, despite being now around 85 years old, and having been posted from France to the USA and back to England over the course of that time. It appears that it remained in Albert Morancé's personal possession until 1949, when he presented it to a young American friend, William Sutton. Sutton in turn sent it home as a Christmas gift to his family, with an excited letter in which he writes, "These 50 etchings in water color are priceless now because the artist is dead and this is the last collection (and the best) of his work. The editor, Monsieur Morancé, told me that every one is original and signed by the artist. Each etching expresses the quaintness found in every quarter of Paris. I have been to several of the places pictured and they are exactly like that."

Inscription from Albert Morancé on the verso of the half-title

In fact the etchings are signed in the plate, not hand-signed. Each one was printed by Eugène Véder himself on his own hand press - an incredible labour to achieve a total of 26,250 perfect prints, each painstakingly colour-registered. No wonder he didn't feel like signing them too!

Eugène Véder, La place du Parvis Notre-Dame

Etching, 1927

Eugène Véder, Sur le Pont-Neuf

Etching, 1927

It has been quite hard to find out all that much about Eugène Véder. Every website which lists or mentions him has his date of death wrong, repeating a rare mistake in the art reference bible, Bénézit. This has him living to be 100, and dying in 1976. As we know from William Sutton's letter, written on November 22, 1949, Véder was already dead by then. In fact he died in 1936.

Eugène Véder, La Seine au quai Saint-Michel

Etching, 1927

Eugène Véder, Le quai de Béthune

Etching, 1927

Perhaps not surprisingly, the only writing of any substance I have found about Véder is in Byblis, accompanying his etching of La rue Saint-Denis. It is an essay by Robert Vernand, entitled "Eugène Veder, Parisien" (Burnand never gives Véder the acute accent). He writes:

Tous les jours, j'imagine, Veder quitte son atelier de la Montagne Saint-Geneviève, cette petite place de l'Estrapade qui, malgré son nom redoutable, dort à l'ombre de paisibles catalpas. Il s'en va, son carton sous les bras, ou sa boîte d'aquarelle. Il muse le nez en l'air, descend la rue Mouffetard, bavarde avec les commères, marchande des fruits aux baladeuses et, si besoin est, boit un verre sur le zinc. Et son oeil note et son crayon enregistre; il dessine et il peint dans un coin, installé vaille que vaille. "Every day, I guess, Véder leaves his studio in the Montagne Saint-Genevieve, in the little place de l'Estrapade which, despite its formidable name, sleeps in the shade of tranquil catalpa trees. He sorties out with his portfolio under his arms, or his box of watercolors. He dawdles, nose in the air, down the Rue Mouffetard, chats with the gossips, from the fruit sellers to the idlers, and, if necessary, pops in for a drink at the bar. And his eye notes and his pencil and records, and he paints in a corner, installed any old how."

Eugène Véder, La porte de Bagnolet

Etching, 1927

Eugène Véder, La place des Vosges

Etching, 1927

Burnand compares Véder's art to that of Jean-François Raffaëlli, the great Impressionist pioneer of the colour etching, and it is a comparison that also occurred to me. Interestingly, the earliest work by Véder mentioned by Bénézit is a 1913 drawing in coloured crayons entitled Les chiffoniers (The rag-and-bone men), a subject that also attracted Raffaëlli.

Jean-François Raffaëlli, Le chiffonier

Etching with aquatint, 1911

Eugène Véder, La rue Saint-Médard (Marché des Chiffoniers)

Etching, 1927

A second work mentioned by Bénézit places Eugène Véder at Arras in 1916; it is a crayon and watercolour drawing of Arras, porte des Trois Visages.

Eugène Véder, Le Marché aux Oiseaux

Etching, 1927

Eugène Véder, La place de la Madeleine (Marché aux Fleurs)

Etching, 1927

Eugène Louis Véder was born in Saint-Germain-en-Laye in 1876. As Bénézit attests, his artistic career stretches back before WWI, but I am not sure how active he was as an artist at this time - after all, he was 38 when the war broke out, so if he had been working as an artist much before that time, one would expect more evidence of it.

Eugène Véder, Le parc Monceau

Etching, 1927

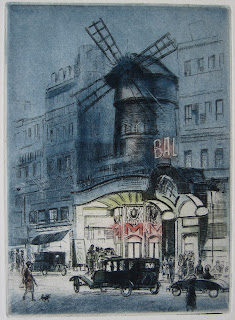

Eugène Véder, La place Blanche

Etching, 1927

Whatever the facts, Eugène Véder is essentially an artist of the 1920s. He exhibited with the Salon des Artistes Français from 1922, becoming a member of the society, and receiving a bronze medal in 1923 and a silver in 1925.

Eugène Véder, Le Moulin de la Galette

Etching, 1927

Eugène Véder, La Pointe Saint--Eustache

Etching, 1927

Véder received prestigious commissions for etchings of Paris, for instance from the Chalcographie du Louvre, enabling him to establish himself in a studio in the place de l'Estrapade in the Latin Quarter. However his chief patron was certainly Albert Morancé, who promoted Véder's art in Byblis, and commissioned his masterwork, Paris: cinquante eaux-fortes en couleurs. These etchings remain one of the finest artistic records of the city of Paris. As Robert Burnand puts it, "With a few pencil strokes he evokes the clutter and bustle [of the city] - with a single line, he opens up infinite horizons."

Eugène Véder, Le Pont des Arts et l'Institut

Etching, 1927

Eugène Véder, La Tour Eiffel vue d'Auteuil

Etching, 1927

Les Amis du vieux Châtillon published a book on Véder in 1993,

Eugène Véder 1876-1936, but unfortunately I have not been able to track down a copy. Véder's son, Lucien Véder, was also an etcher. Taught by his father, he used the pseudonym Legarf so as not to tread on his father's toes.